What you will find on this page: LATEST NEWS; Fossil fuel emissions have stalled; Analysis: Record surge of clean energy in 2024 halts China’s CO2 rise; does the world need hydrogen?; Mapped: global coal trade; Complexity of energy systems (maps); Mapped: Germany’s energy sources (interactive access); Power to the people (video); Unburnable Carbon (report); Stern Commission Review; Garnaut reports; live generation data; fossil fuel subsidies; divestment; how to run a divestment campaign guide; local council divestment guide; US coal plant retirement; oil conventional & unconventional; CSG battle in Australia (videos); CSG battle in Victoria; leasing maps for Victoria; coal projects Victoria

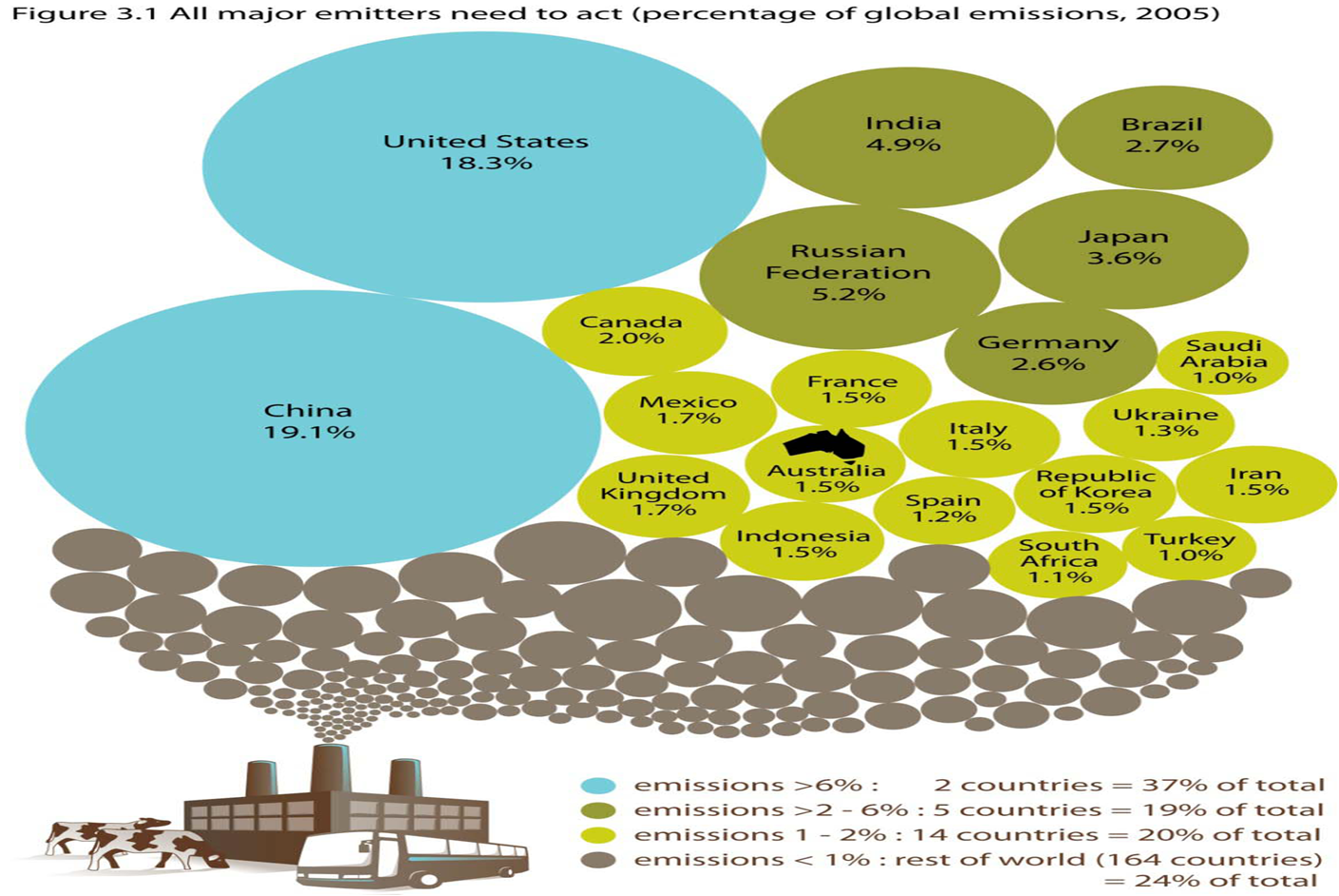

Huge task to decarbonise

Source: Australian Delegation presentation to international forum held in Bonn in May 2012

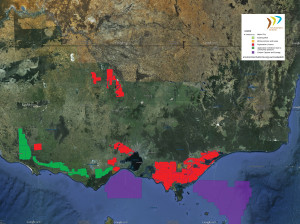

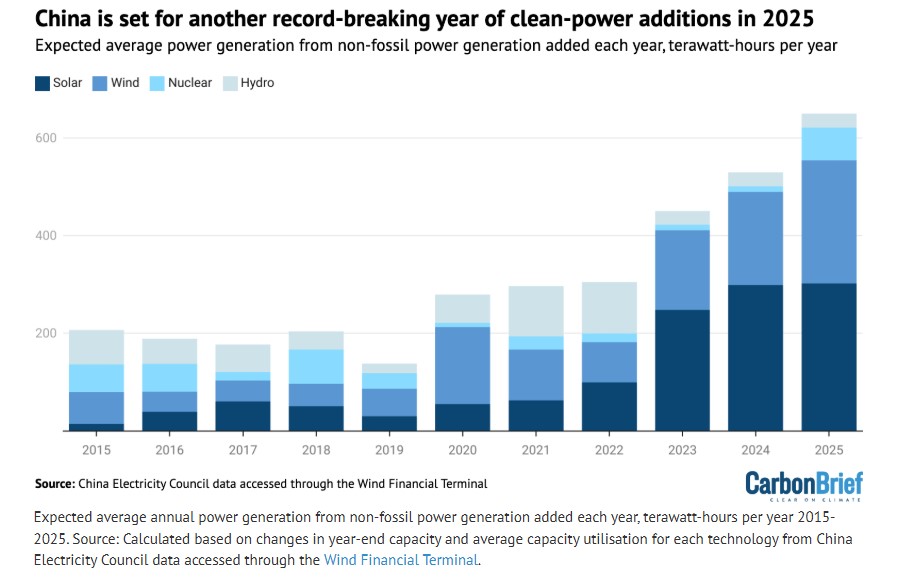

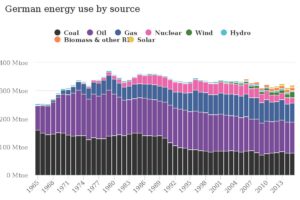

Latest News 12 February 2026, Carbon Brief: Analysis: Trump has overseen larger coal decline than any other US president. Donald Trump has overseen a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity than any other US president, according to Carbon Brief analysis. His administration’s latest efforts to roll back US climate policy have been presented by interior secretary Doug Burgum as an opportunity to revive “clean, beautiful, American coal”. The administration is in the process of attempting to repeal the 2009 “endangerment” finding, which is the legal underpinning of many federal climate regulations. On 11 February, the White House issued an executive order on “America’s beautiful clean coal power generation fleet”, calling for government contracts and subsidies to keep plants open. On the same day, Trump was presented with a trophy by coal-mining executives declaring him to be the “undisputed champion of beautiful clean coal”. These words are in sharp contrast to Trump’s record in office, with a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity under his leadership than any other president, as shown in the figure below. This is because coal plants have been uneconomic to operate compared with cheaper gas and renewables – and because most of the US coal fleet is extremely old. Read more here 17 October 2025, Global Maritine Forum: Negotiations at International Maritime Organization adjourn without a decision on shipping’s Net-Zero Framework. At this week’s negotiations at the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) MEPC 2nd Extraordinary Meeting, Member States that agreed decisively on the framework in April were confronted by extraordinary political challenges to its adoption. “Today’s adjournment is a disappointing setback for shipping, but not the end of this journey. The adjournment for a full year creates serious challenges for meeting the timelines in the Net-Zero Framework agreed in April and will make delivery of the sector’s decarbonisation targets even more challenging,” says Global Maritime Forum director of decarbonisation Jesse Fahnestock. “We encourage Member States that agreed on the framework in April to re-confirm their commitment to multilateralism and continue the urgent work of developing guidelines and adopting a regulatory framework that can deliver on the IMO’s unanimously agreed Greenhouse Gas Strategy.” The MEPC will continue to work on guidelines for implementation of the Net-Zero Framework, and it is essential to complete the design of rewards for Zero and Near-Zero Fuels, define use of funds for a just and equitable transition, and provide clarity on emissions accounting as soon as possible. Clear and robust guidelines can help pave the way for adoption next year. In the meantime, the actions of industry, nations and regions will play a crucial role in sustaining progress towards that goal. We call on industry to keep exploring innovative decarbonisation solutions, and forward-looking states to champion ambitious policies that can drive progress in shipping’s transition to net zero. Read more here 21 April 2025, Renew Economy: Taylor’s nuclear spin is an intense form of greenwashing from a party hellbent on fossil fuels. We’re deep into what’s been described as “debate season”, and for a political party that began this election campaign on shaky ground, there are increasing signs of desperation and weirdness coming from the Coalition. Part of the party’s plan to keep coal and gas at their maximum levels over the coming decades has been offering a false, manufactured vision of nuclear power for the future. It’s an intense form of greenwashing and the important thing to remember is that the party that spent nine years not legalising nuclear power when they were in government will absolutely never, ever decide to do that if they were to win power again. Honestly, Labor is more likely to eventually legalise nuclear power than the Coalition is. The dynamic of fabricated promises was demonstrated perfectly on the ABC’s 730 program debate between shadow treasurer and former energy minister Angus Taylor, and Treasurer Jim Chalmers. Taylor has a long and amusing history of gaffes and mistakes in energy, and during this debate, he claimed: “We know that by building seven 2 gigawatt baseload generators which will deliver a return to shareholders, which will be the taxpayers – they’ll deliver a return – that’s how they’re paid for.” The Global Energy Monitor’s amazing nuclear power tracker lets us quickly check out how large nuclear power units tend to be, and we can see that they’re consistently smaller than two gigawatts: Read more here: 21 April 2025, Renew Economy: “Damaging, regressive policies:” Coalition scores 1/100 on climate and nature, Labor scrapes a pass. One election cycle after the federal Coalition was Australian tossed out of government following a voter backlash against inaction on climate and renewables, the Liberal National Party has scored just 1 point out of 100 for its policies supporting climate and renewables.The “woeful score” was awarded to the Coalition as part of the Australian Conservation Foundation’s election scorecard, described as an issue-based assessment of how closely parties and candidates align with the ACF’s own policy agenda for protecting nature and acting on climate.ACF CEO Kelly O’Shanassy says it’s the lowest mark the election scorecard has ever given the Coalition – even lower than the 4/100 awarded in 2019, the year Tony Abbott lost his “safe” Liberal seat of Warringah in a protest vote against his climate wrecking efforts while prime minister. “The Coalition’s woeful score reflects its damaging, regressive policies: climate wrecking gas, and expensive and risky nuclear energy over clean, affordable renewables, coupled with cuts to environment protection at the behest of the fossil fuel industry,” O’Shanassy said on Tuesday. O’Shanassy says the Coalition scored its single point for acknowledging concerns about details of the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal that could saddle Australia with high levels of nuclear waste from overseas. But that is it. “Australia would be a worse place to live under the Coalition’s policies,” she said. The scorecard is based on surveys of the major parties and independent candidates in key seats to determine where they stand on the 16 outcomes in ACF’s national agenda. Read more here: 19 February, Politico: US succeeds in erasing climate from global energy body’s priorities. Trump’s energy chief had threatened to leave the International Energy Agency if it continued to focus on climate. The United States has succeeded in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency, following a tense ministerial meeting in Paris that reflected a dramatic shift in political mood around the clean energy transition. In the chair’s summary released at the end of the two-day meeting, addressing climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities. Instead, the document focuses on energy security, resilience, critical minerals and electricity systems. The development, which comes after the U.S. threatened to leave the agency if it continued to focus on climate change, is a remarkable turnaround from the last ministerial two years ago, when addressing the climate crisis and phasing out fossil fuels was named as the IEA’s top priority. Unusually, there was no joint communique from the ministers at the end of this week’s meeting. The chair’s summary mentioned climate change just once, saying “a large majority of ministers stressed the importance of the energy transition to combat climate change and highlighted the global transition to net zero emissions in line with COP28 outcomes.” Read more here 12 February 2026, Carbon Brief: Analysis: Trump has overseen larger coal decline than any other US president. Donald Trump has overseen a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity than any other US president, according to Carbon Brief analysis. His administration’s latest efforts to roll back US climate policy have been presented by interior secretary Doug Burgum as an opportunity to revive “clean, beautiful, American coal”. The administration is in the process of attempting to repeal the 2009 “endangerment” finding, which is the legal underpinning of many federal climate regulations. On 11 February, the White House issued an executive order on “America’s beautiful clean coal power generation fleet”, calling for government contracts and subsidies to keep plants open. On the same day, Trump was presented with a trophy by coal-mining executives declaring him to be the “undisputed champion of beautiful clean coal”. These words are in sharp contrast to Trump’s record in office, with a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity under his leadership than any other president, as shown in the figure below. This is because coal plants have been uneconomic to operate compared with cheaper gas and renewables – and because most of the US coal fleet is extremely old. Read more here 15 December 2025, Reuters: US demands EU exempt its gas from methane emissions law, document shows. The U.S. has demanded that the European Union exempt its oil and gas from obligations under the bloc’s methane emissions law on fuel imports until 2035, a U.S. government document seen by Reuters showed. Starting this year, the EU requires importers of oil and gas to Europe to monitor and report methane emissions associated with those imports, in a bid to curb emissions of the potent planet-warming gas. The world-first climate policy has faced opposition from U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright, who has called it impossible to implement and warned it could disrupt U.S. gas supplies to Europe. European countries have increased imports of U.S. liquefied natural gas as they phase out oil and gas from Russia. The U.S. document said that in the absence of a “full repeal” of the EU law, Washington was asking the EU to “delay requiring U.S. emissions data reporting under the EUMR [EU Methane Regulation] until October 2035.” “The EU Methane Regulations is a critical non-tariff trade barrier that imposes an undue burden on U.S. exporters and our trade relationship,” said the document, circulated to EU member governments ahead of a meeting of their energy ministers in Brussels on Monday. Read more here 7 November 2025, The Guardian: Net zero is an insidious loophole that distracts from the scientific imperative to eliminate fossil fuels. History tells us that polite incrementalism and political kowtowing will prevail at Cop30 – even as catastrophe unfolds around us. Despite 30 years of UN climate summits, about half of the carbon dioxide accumulated in the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution has been emitted since 1990. Incidentally, 1990 was the year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the global authority on climate change science – released its First Assessment Report confirming the threat of human-caused global warming. As scientists all over the world prepare the IPCC’s Seventh Assessment Report, we do so knowing that our work is still being overshadowed by politics. Despite all the well-intentioned half-measures, the truth is that the world is still disastrously off track to limit dangerous climate change. In the avalanche of technical reports released before Cop30, the World Meteorological Organization stated that CO2 concentrations reached a record high of 423.9 parts per million in 2024, with the growth rate from 2023 to 2024 surging by the largest yearly increase since modern measurements began in 1957. The latest figures from Global Carbon Project show that 90% of total global CO2 emissions in 2024 were generated from the burning of fossil fuels, with the remaining 10% coming from land-use changes including deforestation and wildfires. Instead of focusing on economic incentives to encourage the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, climate policies are heavily reliant on feelgood “nature positive” solutions that aim to neutralise carbon emissions by essentially planting trees instead of reducing industrial emissions. While the protection, expansion and rehabilitation of natural carbon sinks like forests and wetlands is an inherently good thing to do, researchers have shown that there is not enough land to meet the global goal of net zero emissions using nature-based solutions alone. Read more here 19 February, Politico: US succeeds in erasing climate from global energy body’s priorities. Trump’s energy chief had threatened to leave the International Energy Agency if it continued to focus on climate. The United States has succeeded in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency, following a tense ministerial meeting in Paris that reflected a dramatic shift in political mood around the clean energy transition. In the chair’s summary released at the end of the two-day meeting, addressing climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities. Instead, the document focuses on energy security, resilience, critical minerals and electricity systems. The development, which comes after the U.S. threatened to leave the agency if it continued to focus on climate change, is a remarkable turnaround from the last ministerial two years ago, when addressing the climate crisis and phasing out fossil fuels was named as the IEA’s top priority. Unusually, there was no joint communique from the ministers at the end of this week’s meeting. The chair’s summary mentioned climate change just once, saying “a large majority of ministers stressed the importance of the energy transition to combat climate change and highlighted the global transition to net zero emissions in line with COP28 outcomes.” Read more here 12 February 2026, Carbon Brief: Analysis: Trump has overseen larger coal decline than any other US president. Donald Trump has overseen a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity than any other US president, according to Carbon Brief analysis. His administration’s latest efforts to roll back US climate policy have been presented by interior secretary Doug Burgum as an opportunity to revive “clean, beautiful, American coal”. The administration is in the process of attempting to repeal the 2009 “endangerment” finding, which is the legal underpinning of many federal climate regulations. On 11 February, the White House issued an executive order on “America’s beautiful clean coal power generation fleet”, calling for government contracts and subsidies to keep plants open. On the same day, Trump was presented with a trophy by coal-mining executives declaring him to be the “undisputed champion of beautiful clean coal”. These words are in sharp contrast to Trump’s record in office, with a larger fall in coal-fired power capacity under his leadership than any other president, as shown in the figure below. This is because coal plants have been uneconomic to operate compared with cheaper gas and renewables – and because most of the US coal fleet is extremely old. Read more here 21 January 2026, SBS News: $1.5 billion for a seat: Is Trump’s new Board of Peace an ‘irreparable’ threat? Experts say Trump’s new body is susceptible to nepotism and corruption, and could undermine the role of the United Nations. A Donald Trump-led organisation that seeks to facilitate peace in the Middle East and beyond could, in fact, do the opposite and cause damage to the international order, experts warn. Trump has invited world leaders to join his so-called ‘Board of Peace’, an entity that started with a mandate to oversee the administration and reconstruction of Gaza, but has quickly ballooned in its planned remit. Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas signed off on Trump’s plan, which says a Palestinian technocratic administration will be overseen by an international board, which will supervise Gaza’s governance for a transitional period. Diplomats have said the plan risks undermining existing United Nations structures, with reports that permanent seats could be bought for a billion dollars, according to media reports. Hugh Lovatt, a senior policy fellow with the Middle East and North Africa Program at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said officials around the world have been privately concerned the Board of Peace is a “Trumpian effort to replace the United Nations”. “Those concerns are indeed borne out by virtue of the sheer number of UN members that are now invited to this Board of Peace,” he told ABC radio. “It is clear that Trump himself has greater aspirations and has talked about the Board of Peace potentially taking charge to some extent in Ukraine and potentially also Venezuela and in Iran.” Read more here 22 December 2025, The Guardian: Trump’s shuttering of the National Center for Atmospheric Research is Stalinist. This is the latest in the relentless purge of climate researchers who refuse to be co-opted by the fossil fuel industry. The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin would no doubt have understood and even appreciated the latest attack by the Trump administration on climate researchers and their work. The National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, is to be dismantled after more than 50 years at the forefront of global research on climate science and monitoring. This is the latest step in the administration’s climate Lysenkoism and its relentless purge of climate researchers who refuse to be co-opted into its quest for American energy dominance though fossil fuels. Stalin’s embrace of the work of Trofim Denisovitch Lysenko, who wrongly believed that wheat could inherit characteristics acquired by previous generations, underpinned policies that failed to prevent crop failures and millions of deaths from famine during the 1930s. Scientists who opposed Lysenkoism were denounced, fired, imprisoned and even executed. While Trump has not gone as far as Stalin, his administration’s persecution of climate researchers could ultimately lead to many millions of deaths from increases in extreme weather and sea level rise in the United States and across the world. Read more here 27 January 2025, Carbon Brief: A record surge of clean energy kept China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions below the previous year’s levels in the last 10 months of 2024. However, the new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures and commercial data, shows the tail end of China’s rebound from zero-Covid in January and February, combined with abnormally high growth in energy demand, stopped CO2 emissions falling in 2024 overall. While China’s CO2 output in 2024 grew by an estimated 0.8% year-on-year, emissions were lower than in the 12 months to February 2024. Other key findings of the analysis include: As ever, the latest analysis shows that policy decisions made in 2025 will strongly affect China’s emissions trajectory in the coming years. In particular, both China’s new commitments under the Paris Agreement and the country’s next five-year plan are being prepared in 2025. Read More Here 3 November 2020, Carbon Brief: Hydrogen gas has long been recognised as an alternative to fossil fuels and a potentially valuable tool for tackling climate change. Now, as nations come forward with net-zero strategies to align with their international climate targets, hydrogen has once again risen up the agenda from Australia and the UK through to Germany and Japan. In the most optimistic outlooks, hydrogen could soon power trucks, planes and ships. It could heat homes, balance electricity grids and help heavy industry to make everything from steel to cement. But doing all these things with hydrogen would require staggering quantities of the fuel, which is only as clean as the methods used to produce it. Moreover, for every potentially transformative application of hydrogen, there are unique challenges that must be overcome. In this in-depth Q&A – which includes a range of infographics, maps and interactive charts, as well as the views of dozens of experts – Carbon Brief examines the big questions around the “hydrogen economy” and looks at the extent to which it could help the world avoid dangerous climate change. Access full article here Fossil fuel emissions have stalled 14 November 2016, The Conversation, Fossil fuel emissions have stalled: Global Carbon Budget 2016. For the third year in a row, global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry have barely grown, while the global economy has continued to grow strongly. This level of decoupling of carbon emissions from global economic growth is unprecedented.Global CO₂ emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels and industry (including cement production) were 36.3 billion tonnes in 2015, the same as in 2014, and are projected to rise by only 0.2% in 2016 to reach 36.4 billion tonnes. This is a remarkable departure from emissions growth rates of 2.3% for the previous decade, and more than 3% during the 2000’s. Read More here Do you want to understand the complexity of energy systems which support our high consumption lifestyles? Most people don’t give too much thought to where their electricity comes from. Flip a switch, and the lights go on. That’s all. The origins of that energy, or how it actually got into our homes, is generally hidden from view. This link will take you to 11 maps which explain energy in America (it is typical enough as an example of a similar lifestyle as Australia – when I find maps for Oz I’ll add them in) e.g. above map showing the coal plants in the US. Source: Vox Explainers Mapped: how Germany generates its electricity – another example Power to the People – Lock the Gate looks back at the wins of 2015 And there’s lots more coming up in 2016. Some of the big priorities coming up next for the “Lock the Gate” movement are: If you want to give “Lock the Gate” your support – go here for more info This new report reveals that the pollution from Australia’s coal resources, particularly the enormous Galilee coal basin, could take us two-thirds of the way to a two degree rise in global temperature. To Read More and download report The 2006 UK government commissioned Stern Commission Review on the Economics of Climate Change is still the best complete appraisal of global climate change economics. The review broke new ground on climate change assessment in a number of ways. It made headlines by concluding that avoiding global climate change catastrophe was almost beyond our grasp. It also found that the costs of ignoring global climate change could be as great as the Great Depression and the two World Wars combined. The review was (still is) in fact a very good assessment of global climate change, which inferred in 2006 that the situation was a global emergency. Read More here The Garnaut Climate Change Review was commissioned by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments in 2007 to conduct an independent study of the impacts of climate change on the Australian economy. Prof. Garnaut presented The Garnaut Climate Change Review: Final Report to the Australian Prime Minister, Premiers and Chief Ministers in September 2008 in which he examined how Australia was likely to be affected by climate change, and suggested policy responses. In November 2010, he was commissioned by the Australian Government to provide an update to the 2008 Review. In particular, he was asked to examine whether significant changes had occurred that would affect the analysis and recommendations from 2008. The final report was presented May 2011. Since then the Professor has regularly participated in the debate of fossil fuel reduction, as per his latest below: To access his reports; interviews; submissions go here 27 May 2015, Renew Economy, Garnaut: Cost of stranded assets already bigger than cost of climate action. This is one carbon budget that Australia has already blown. Economist and climate change advisor Professor Ross Garnaut has delivered a withering critique of Australia’s economic policies and investment patterns, saying the cost of misguided over-investment in the recent mining boom would likely outweigh the cost of climate action over the next few decades. Read More here Live generation of electricity by fuel type Fossil Fuel Subsidies – The Age of entitlement continues 24 June 2014, Renew Economy, Age of entitlement has not ended for fossil fuels: A new report from The Australia Institute exposes the massive scale of state government assistance, totalling $17.6 billion over a six-year period, not including significant Federal government support and subsidies. Queensland taxpayers are providing the greatest assistance by far with a total of $9.5 billion, followed by Western Australia at $6.2 billion. The table shows almost $18 billion dollars has been spent over the past 6 years by state governments, supporting some of Australia’s biggest, most profitable industries, which are sending most of the profits offshore. That’s $18 billion dollars that could have gone to vital public services such as hospitals, schools and emergency services. State governments are usually associated with the provision of essential services like health and education so it will shock taxpayers to learn of the massive scale of government handouts to the minerals and fossil fuel industries. This report shows that Australian taxpayers have been misled about the costs and benefits of this industry, which we can now see are grossly disproportionate. Each state provides millions of dollars’ worth of assistance to the mining industry every year, with the big mining states of Queensland and Western Australia routinely spending over one billion dollars in assistance annually. Read More here – access full report here What is fossil fuel divestment? Local Governments ready to divest Aligning Council Money With Council Values A Guide To Ensuring Council Money Isn’t Funding Climate Change. 350.org Australia – with the help of the incredible team at Earth Hour – has pulled together a simple 3-step guide for local governments interested in divestment. The movement to align council money with council values is constantly growing in Australia. It complements the existing work that councils are doing to shape a safe climate future. It can also help to reshape the funding practices of Australia’s fossil fuel funding banks. The steps are simple. The impact is huge.The guide can also be used by local groups who are interested in supporting their local government to divest as a step-by-step reference point. Access guide here How coal is staying in the ground in the US Sierra Club Beyond Coal Campaign May 2015, Politico, Michael Grunwald: The war on coal is not just political rhetoric, or a paranoid fantasy concocted by rapacious polluters. It’s real and it’s relentless. Over the past five years, it has killed a coal-fired power plant every 10 days. It has quietly transformed the U.S. electric grid and the global climate debate. The industry and its supporters use “war on coal” as shorthand for a ferocious assault by a hostile White House, but the real war on coal is not primarily an Obama war, or even a Washington war. It’s a guerrilla war. The front lines are not at the Environmental Protection Agency or the Supreme Court. If you want to see how the fossil fuel that once powered most of the country is being battered by enemy forces, you have to watch state and local hearings where utility commissions and other obscure governing bodies debate individual coal plants. You probably won’t find much drama. You’ll definitely find lawyers from the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, the boots on the ground in the war on coal. Read More here Oil – conventional & unconventional May 2015, Oil change International Report: On the Edge: 1.6 Million Barrels per Day of Proposed Tar Sands Oil on Life Support. The Canadian tar sands is among the most carbon-intensive, highest-cost sources of oil in the world. Even prior to the precipitous drop in global oil prices late last year, three major projects were cancelled in the sector with companies unable to chart a profitable path forward. Since the collapse in global oil prices, the sector has been under pressure to make further cuts, leading to substantial budget cuts, job losses, and a much more bearish outlook on expansion projections in the coming years. Read full report here. For summary of report USA Sierra Club Beyond Oil Campaign Coal Seam Gas battle in Australia Lock the Gate Alliance is a national coalition of people from across Australia, including farmers, traditional custodians, conservationists and urban residents, who are uniting to protect our common heritage – our land, water and communities – from unsafe or inappropriate mining for coal seam gas and other fossil fuels. Read more about the missions and principles of Lock the Gate. Access more Lock the Gate videos here. Access Lock the Gate fact sheets here 2014: Parliament of Victoria Research Paper: Unconventional Gas: Coal Seam Gas, Shale Gas and Tight Gas: This Research Paper provides an introduction and overview of issues relevant to the development of unconventional gas – coal seam, shale and tight gas – in the Australian and specifically Victorian context. At present, the Victorian unconventional gas industry is at a very early stage. It is not yet known whether there is any coal seam gas or shale gas in Victoria and, if there is, whether it would be economically viable to extract it. A moratorium on fracking has been in place in Victoria since August 2012 while more information is gathered on potential environmental risks posed by the industry. The parts of Victoria with the highest potential for unconventional gas are the Gippsland and Otway basins. Notably, tight gas has been located near Seaspray in Gippsland but is not yet being produced. There is a high level of community concern in regard to the potential impact an unconventional gas industry could have on agriculture in the Gippsland and Otway regions. Industry proponents, however, assert that conventional gas resources are declining and Victoria’s unconventional gas resources need to be ascertained and developed. Read More here 28 January 2015, ABC News, Coal seam gas exploration: Victoria’s fracking ban to remain as Parliament probes regulations: A ban on coal seam gas (CSG) exploration will stay in place in Victoria until a parliamentary inquiry hands down its findings, the State Government has promised. There is a moratorium on the controversial mining technique, known as fracking, until the middle of 2015. The Napthine government conducted a review into CSG, headed by former Howard government minister Peter Reith, which recommended regulations around fracking be relaxed. Labor was critical of the review, claiming it failed to consult with farmers, environmental scientists and local communities. Read more here Keep up to date and how you can be involved here Friends of the Earth Melbourne Coal & Gas Free Victoria 20 May 2015, FoE, Inquiry into Unconventional Gas: Check here for details on the Victorian government’s Inquiry into unconventional gas. The public hearings have not yet started, however the Terms of Reference have been released. The state government’s promised Inquiry into Unconventional Gas has now been formally announced, with broad terms of reference (TOR). FoE’s response to the TOR is available here. The Upper House Environment and Planning Committee will manage the Inquiry. You can find the Inquiry website here. The final TOR will be determined by the committee. Significantly, it is a cross party committee. The Chair is a Liberal (David Davis), and there is one National (Melinda Bath), one Green (Samantha Dunn), three from the ALP (Gayle Tierney, Harriet Shing, Shaun Leane), an additional MP from the Liberals (Richard Dalla-Riva), and one MP from the Shooters Party (Daniel Young). Work started by the previous government, into water tables and the community consultation process run by the Primary Agency, will be released as part of the inquiry.The moratorium on unconventional gas exploration will stay in place until the inquiry delivers its findings. The interim report is due in September and the final report by December. There is the possibility that the committee will amend this timeline if they are overwhelmed with submissions or information. Parliament will then need to consider the recommendations of the committee and make a final decision about how to proceed. This is likely to happen when parliament resumes after the summer break, in early 2016. Quit Coal is a Melbourne-based collective that campaigns against the expansion of the coal and unconventional gas industries in Victoria. Quit Coal uses a range of tactics to tackle this problem. We advise the broader Victorian community about plans for new coal and unconventional gas projects, we put pressure on our government to stop investing in these projects, and we help to inform and mobilise Victorian communities so they can campaign on their own behalf. We focus on being strategic, creative, and as much as possible, fun! The above screen shot is of the Victorian State government’s Mining Licences Near Me site. Go to this link to see what is happening in your area Environment Victoria’s campaign CoalWatch is an interactive resource that tracks the coal industry’s expansion plans and helps builds a movement to stop these polluting developments. CoalWatch provides a way for everyday Victorians to keep track of the coal industry’s ambitious expansion plans. To check what tax-payer money has been pledged to brown coal projects and the coal projects industry is spruiking to our politicians. Here’s another map via EV website (go to their website and you should be able to get better detail from Google Maps: Red areas: Exploration licences (EL). These areas are held by companies to undertake exploration activity. A small bond is held by government in case of any damage. If a company wants to progress the project it needs to obtain a mining licence. Exploration Licence applications are marked with an asterix in the Places Index eg. EL4684*. Yellow areas: Mining Licences (MIN). A mining licence is granted with the expectation that mining will occur. A larger bond is paid to government. Green areas: Exploration licences that have been withdrawn or altered due to community concern. Green outline: Existing mines within Mining Licences. Purple areas: Geological Carbon Storage Exploration areas for carbon capture and storage. On-shore areas have been released by the State Government, while off-shore areas have been released by the Federal Government. The Coal Watch wiki tracks current and future Victorian coal projects, whether they are power stations, coal mines, proposals to export coal or some other inventive way of burning more coal. To get the full picture of coal in Victoria visit our wiki page. Get more info and see the full list of Exploration Licences current at 17 August 2012 here August 2015, Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis – powerpoint: Changing Dynamics in the Global Seaborne Thermal Coal Markets and Stranded Asset Risk. Information from one of the slides follows. To view full presentation go here Economic Implications for Australia 83% of Australian coal mines are foreign owned, hence direct leverage of fossil fuels to the ASX is relatively small at 1-2%. However, for Australia the exposure is high, time is needed for transition and the new industry opportunities are significant: 1. Energy Infrastructure: Australia spends $5-10bn pa on electricity / grid sector, much of it a regulated asset base that all ratepayers fund much of it stranded. BNEF estimate of Australia’s renewable energy infrastructure investment for 2015-2020 was cut 30% from A$20bn post RET. Lost opportunities. 2. Direct employment: The ABS shows a fall of ~20k from the 2012 peak of 70K from coal mining across Australia, and cuts are ongoing. Indirect employment material. 3. Terms of trade: BZE estimates the collapse in the pricing of iron ore, coal and LNG cuts A$100bn pa from Australia’s export revenues by 2030, a halving relative to government budget estimates of 2013/14. Coal was 25% of NSW’s total A$ value of exports in 2013/14 (38% of Qld). Australia will be #1 globally in LNG by 2018. 4. The financial sector: is leveraged to mining and associated rail port infrastructure. WICET 80% financed by banks, mostly Australian. Adani’s Abbot Point Port is foreign owned, but A$1.2bn of Australian sourced debt. Insurance firms and infrastructure funds are leveraged to fossil fuels vs little RE infrastructure assets. BBY! 5. Rehabilitation: $18bn of unfunded coal mining rehabilitation across Australia. 6. Economic growth: curtailed as Australia fails to develop low carbon industries. Analysis: Record surge of clean energy in 2024 halts China’s CO2 rise

In-depth Q&A: Does the world need hydrogen to solve climate change?

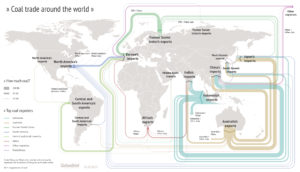

3 May 2016, Carbon Brief, The global coal trade doubled in the decade to 2012 as a coal-fueled boom took hold in Asia. Now, the coal trade seems to have stalled, or even gone into reverse. This change of fortune has devastated the coal mining industry, with Peabody – the world’s largest private coal-mining company – the latest of 50 US firms to file for bankruptcy. It could also be a turning point for the climate, with the continued burning of coal the biggest difference between business-as-usual emissions and avoiding dangerous climate change. Carbon Brief has produced a series of maps and interactive charts to show how the global coal trade is changing. As well as providing a global overview, we focus on a few key countries: Read More here

3 May 2016, Carbon Brief, The global coal trade doubled in the decade to 2012 as a coal-fueled boom took hold in Asia. Now, the coal trade seems to have stalled, or even gone into reverse. This change of fortune has devastated the coal mining industry, with Peabody – the world’s largest private coal-mining company – the latest of 50 US firms to file for bankruptcy. It could also be a turning point for the climate, with the continued burning of coal the biggest difference between business-as-usual emissions and avoiding dangerous climate change. Carbon Brief has produced a series of maps and interactive charts to show how the global coal trade is changing. As well as providing a global overview, we focus on a few key countries: Read More here/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3915730/EIA%20coal%20power%20plants.png)

21 April 2015, Climate Council, Will Steffen: Unburnable Carbon: Why we need to leave fossil fuels in the ground.Stern Commission Review

Australia’s Garnaut Review

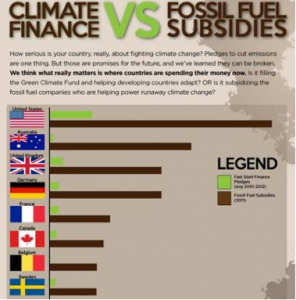

November 2014 – The Fossil Fuel Bailout: G20 subsidies for oil, gas and coal exploration report: Governments across the G20 countries are estimated to be spending $88 billion every year subsidising exploration for fossil fuels. Their exploration subsidies marry bad economics with potentially disastrous consequences for climate change. In effect, governments are propping up the development of oil, gas and coal reserves that cannot be exploited if the world is to avoid dangerous climate change. This report documents, for the first time, the scale and structure of fossil fuel exploration subsidies in the G20 countries. The evidence points to a publicly financed bailout for carbon-intensive companies, and support for uneconomic investments that could drive the planet far beyond the internationally agreed target of limiting global temperature increases to no more than 2ºC. It finds that, by providing subsidies for fossil fuel exploration, the G20 countries are creating a ‘triple-lose’ scenario. They are directing large volumes of finance into high-carbon assets that cannot be exploited without catastrophic climate effects. They are diverting investment from economic low-carbon alternatives such as solar, wind and hydro-power. And they are undermining the prospects for an ambitious climate deal in 2015. Access full report here For the summary on Australia’s susidisation of it’s fossil fuel industry go to page 51 of the report. The report said that the United States and Australia paid the highest level of national subsidies for exploration in the form of direct spending or tax breaks. Overall, G20 country spending on national subsidies was $23 billion. In Australia, this includes exploration funding for Geoscience Australia and tax deductions for mining and petroleum exploration. The report also classifies the Federal Government’s fuel rebate program for resources companies as a subsidy.

November 2014 – The Fossil Fuel Bailout: G20 subsidies for oil, gas and coal exploration report: Governments across the G20 countries are estimated to be spending $88 billion every year subsidising exploration for fossil fuels. Their exploration subsidies marry bad economics with potentially disastrous consequences for climate change. In effect, governments are propping up the development of oil, gas and coal reserves that cannot be exploited if the world is to avoid dangerous climate change. This report documents, for the first time, the scale and structure of fossil fuel exploration subsidies in the G20 countries. The evidence points to a publicly financed bailout for carbon-intensive companies, and support for uneconomic investments that could drive the planet far beyond the internationally agreed target of limiting global temperature increases to no more than 2ºC. It finds that, by providing subsidies for fossil fuel exploration, the G20 countries are creating a ‘triple-lose’ scenario. They are directing large volumes of finance into high-carbon assets that cannot be exploited without catastrophic climate effects. They are diverting investment from economic low-carbon alternatives such as solar, wind and hydro-power. And they are undermining the prospects for an ambitious climate deal in 2015. Access full report here For the summary on Australia’s susidisation of it’s fossil fuel industry go to page 51 of the report. The report said that the United States and Australia paid the highest level of national subsidies for exploration in the form of direct spending or tax breaks. Overall, G20 country spending on national subsidies was $23 billion. In Australia, this includes exploration funding for Geoscience Australia and tax deductions for mining and petroleum exploration. The report also classifies the Federal Government’s fuel rebate program for resources companies as a subsidy.