What you will find on this page: how climate change shapes food insecurity (video); Weather Alert: 4 Corners program (video); About time we got over the “yuk” factor for recycled water (video); Farmers for Climate Action (video); Cool Farm Tool online calulator; Australia’s future food security; WRI Challenge; UNEP summary; BOM water sites: Australia’s water challenge; climate drivers; understanding ENSO (video); groundwater use; water futures; water trading; agriculture; food & water crisis; localising food production; complex food distribution; land use – agriculture & forestry; latest news; also refer to page “impacts observed & projected” as the issues are closely related

Water and climate change

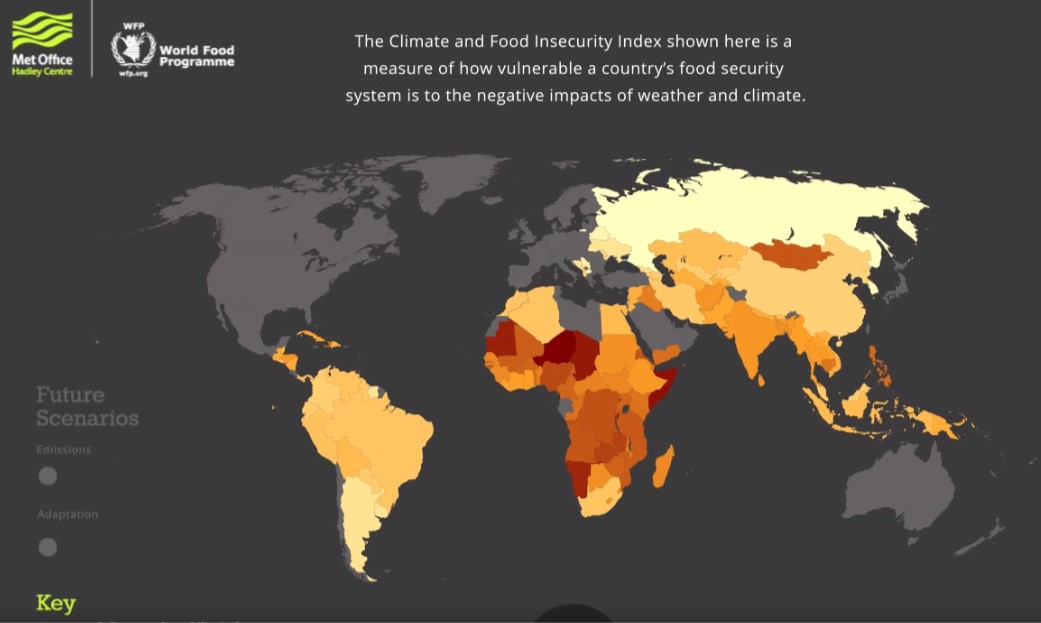

Interactive: How climate change shapes food insecurity across the world

1 December 2015, Carbon Brief: Rising temperatures and more extreme weather are set to increase the pressure on food supplies around the world, risking shortages in the least-developed and developing countries and potentially pushing millions of people into deeper hunger and malnutrition. This is the message from the Met Office and the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), who have joined forces to launch a new interactive map at the COP21 conference underway in Paris. The graphic lets you see where in the world is already vulnerable to food ‘shocks’, and how the picture changes depending on how much action, if any, we take to reduce our emissions. Click on image to open video

Drinking recycled water (or as this video calls it, poop water) isn’t the most appealing notion for many people. But it’s becoming increasingly necessary––this video digs into some of the ways people have come to accept it. Source: Holly Kaw!

Do we drink recycled water in Australia?

Depending on where you live, or where you’ve travelled, there’s a chance you’ve already drunk recycled water.

- NSW – in the Goulburn Valley, wastewater is recycled and returned to the Goulburn River where it can eventually be harvested and processed per usual for drinking.

- Queensland – the Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme is the largest in Australia; the water is currently used for industrial purposes such as power plants but can be used for agriculture and to supplement drinking water supplies in the event of drought.

- Western Australia – the Groundwater Replenishment Scheme has been successfully trialled and full-scale development is proceeding. It returns recycled water to natural groundwater storage (aquifers) for later extraction as drinking water.

Water recycling happens in other regions of Australia but the water is generally directed exclusively for irrigation or industrial use.

Recycled water overseas

- Orange County, California – managed aquifer recharge since 1976.

- Scottsdale, Arizona – managed aquifer recharge since early 1990s.

- North Virginia – reservoir augmentation since 1978.

- Windhoek, Namibia – direct reuse since 1968 and upgraded in 2002.

- Veurne-Ambacht, Belgium – managed aquifer recharge since 2002 (also prevents saltwater intrusion into ground drinking water).

- Singapore – reservoir augmentation since 2003.

- London, UK – upstream wastewater treatment plants discharge into the Thames, so part of the city’s water supplies come indirectly from recycled water.

FCA is an alliance of farmers and leaders in agriculture who are working with their peers, the wider sector and decision-makers to make sure Australia takes the actions necessary to address damage to our climate. FCA is determined to see farmers and agriculture get the support and investment it needs to adapt to a changing climate, as well as be part of the solution. Members are spread far and wide across the country: from the tropical north of Queensland to Tasmania, and from the wine growing regions of Western Australia right across to the sheep and cropping farms of New South Wales. Farmers for Climate Action is an associate member of the National Farmers Federation, and a member of the Climate Action Network Australia (CANA). We work closely with stakeholders within the agricultural and climate realms. Learn more about Farmers for Climate Action here

Feeding a Hungry Nation: Climate change, food and farming in Australia

7 October 2015, Climate Council: The price, quality and seasonality of Australia’s food is increasingly being affected by climate change with Australia’s future food security under threat, our new report has revealed. Australia’s food supply chain is highly exposed to disruption from increasing extreme weather events driven by climate change, with farmers already struggling to cope with more frequent and intense droughts and changing weather patterns.

7 October 2015, Climate Council: The price, quality and seasonality of Australia’s food is increasingly being affected by climate change with Australia’s future food security under threat, our new report has revealed. Australia’s food supply chain is highly exposed to disruption from increasing extreme weather events driven by climate change, with farmers already struggling to cope with more frequent and intense droughts and changing weather patterns.

Climate change is affecting the quality and seasonal availability of many foods in Australia.

- Up to 70% of Australia’s wine-growing regions with a Mediterranean climate (including iconic areas like the Barossa Valley and Margaret River) will be less suitable for grape growing by 2050. Higher temperatures will continue to cause earlier ripening and reduced grape quality, as well as encourage expansion to new areas, including some regions of Tasmania.

- Many foods produced by plants growing at elevated CO2 have reduced protein and mineral concentrations, reducing their nutritional value.

- Harsher climate conditions will increase use of more heat-tolerant breeds in beef production, some of which have lower meat quality and reproductive rates.

- Heat stress reduces milk yield by 10-25% and up to 40% in extreme heatwave conditions.

- The yields of many important crop species such as wheat, rice and maize are reduced at temperatures more than 30°C.

Australia is extremely vulnerable to disruptions in food supply through extreme weather events.

- There is typically less than 30 days supply of non-perishable food and less than five days supply of perishable food in the supply chain at any one time. Households generally hold only about a 3-5 day supply of food. Such low reserves are vulnerable to natural disasters and disruption to transport from extreme weather.

- During the 2011 Queensland floods, several towns such as Rockhampton were cut off for up to two weeks, preventing food resupply. Brisbane came within a day of running out of bread.

Climate change is the most challenging threat to food and water security between now and 2050

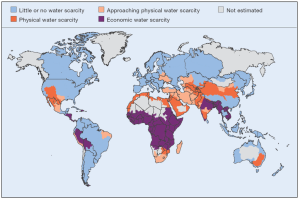

Water risks like stress and variable supply threaten everything from agriculture to industry to energy production. Already, 69 countries and one-quarter of the world’s cropland face high water stress. These challenges will likely become more severe as competition for water increases and climate change shifts precipitation patterns.

The World Economic Forum identified global water crises as one of the top five global risks for businesses. Without tools to evaluate these risks and inform management plans, businesses’ bottom lines will suffer. Read More here

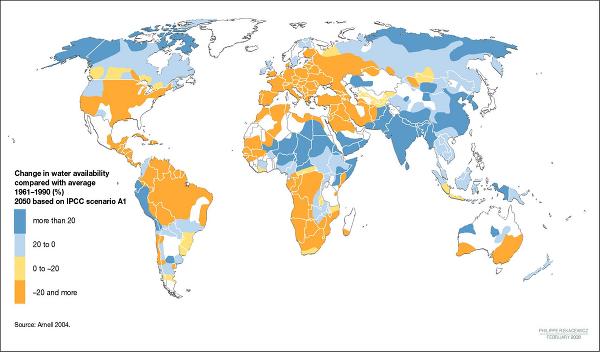

UNEP: The real concern for the future, in the context of changing patterns of rainfall, is the decrease of run-off water which may put at risk large areas of arable land. The map shows how seriously this issue must be taken, while the forecast indicates that some of the richest arable regions (Europe, United States, parts of Brazil, southern Africa) are threatened with a significant reduction of run-off water, resulting in a lack of water for rain-fed agriculture and thus putting millions at risks.

The accelerating changes in our global climate will undoubtedly cause major changes in the patterns of water cycle and geographical distribution, in the near future. Some regions will receive less precipitation, some more, and this will significantly affect agricultural activity. While some regions will see a reduction in arable land, others will have more suitable land for agriculture. It’s likely that certain types of agriculture will migrate and traditional areas for crops will change. In other words, climate change will alter the geography of traditional crop areas, which may impact on the world’s capacity to provide enough food for all.

Since the 1990s, the scientific community has been warning about the rapidly changing climate, endeavouring to convince people to take urgent measures to mitigate the changes. These multiple warnings have been ignored until very recently, but the issue is now a priority with many international organizations. However, all reliable climate scenarios run by the IPCC and published in the fourth assessment reports show the following results:

- agriculture and rural development will be violently hit by climate change

- poverty and under-nourishment will grow with the uncertainty of food supply

- the climatologic regime will imply more risk of vulnerability for both humans and biodiversity

- a reduction of glaciers will imply a growing security risk for hundreds of millions living near coasts.

In other words, ongoing climate change will mean that the water supply for human communities will become more and more uncertain. The IPCC has stated that between 2000 and 2005 in the northern hemisphere, climate change accelerated faster than predicted, with the consequence that the water cycle could change in an unpredictable way, leading to the possibility of increases in extreme weather.

The fear is that with all these changes, even if the quantity of water in the world does not change, the level of accessibility of the theoretically available water may significantly change. Source: UNEP

Future Directions International highlights Australia’s challenge

- Temperature increases, changing rainfall patterns, rising sea levels, extreme weather events and climate variability will impact hydrological cycles and agricultural systems, undermining food and water security.

- The impact of climate change on agricultural production will vary across regions. In some areas changes in the climate will boost food production; however, the net impact on yields is forecast to be overwhelmingly negative.

- Developing countries with a low capacity for mitigation and adaptation measures are expected to bare 70 to 80 per cent of climate change related costs.

- The number of people at risk of hunger may climb by 10 to 20 per cent by 2050 as a result of climate change.

- Implementing mitigation and adaptation strategies can make the agricultural sector more resilient to climate change. Political will and immediate action is required to minimise impacts on food and water security.

BOM water information and update sites

3 August 2015, The Conversation, The role of water in Australia’s uncertain future: If you live in an Australian city, there’s a good chance that your water comes from surface water such as streams, rivers and reservoirs filled by rainfall and runoff. If you live in Perth, much of your water (about 40%) comes from groundwater. But you might be surprised to know that a sizeable proportion of water in Australia came from recycling or desalination in 2013-14. 39% of Perth’s water came from desalination and 41% of Adelaide’s. All cities also used small portions of recycled water: Melbourne (4%), Sydney (7%), southeast Queensland (7%), and Canberra (8%). The Bureau of Meteorology recently released, for the first time, comprehensive national data on these “climate-resilient” water sources, through a new online portal provided as part of the Bureau’s Improving Water Information program. Climate-resilient water sources are those on which climate variability, such as variations in rainfall, temperature and drought, has little or no influence. The data set provides information on two of the most significant such sources: desalination and water recycling.

The Climate Resilient Water Sources web portal is an interactive site providing comprehensive mapping and information of desalinated and recycled water sources for over 350 sites across Australia, both publicly and privately owned and operated. Users can access the portal, to search information on capacity, production, location and use of these alternative water sources across Australia.

How many desalination and recycled water plants does Australia have? Below you can see the amount of desalinated and recycled water sourced for Australia’s cities in 2013–14 from the National Performance Report released in May 2015.

From the Climate Resilient Water Source data we can also see which parts of Australia have the greatest climate resilient capacity compared to their sourced water (including surface, ground, recycled water and desalination). Western Australia has greater climate resilient capacity than its total water sourced in 2013–14, as you can see in the chart below:

We can also see that more than 50% of reported production of recycled or desalinated water in 2012-13 (410,491 ML) was for urban use (residential, domestic, commercial, industrial, municipal). Read More here

- National Overview: Visualise data on capacity, production, water sources and use through national, State and Territory filters.

- Site explorer: Explore sites on an interactive map or table with plant details.

- Data download: Download the full dataset for further information and analysis.

- Contribute: Contribute to our developing dataset with information about your facility.

Improving Water Information: data, status and forecasts

Australia’s variable climate drivers

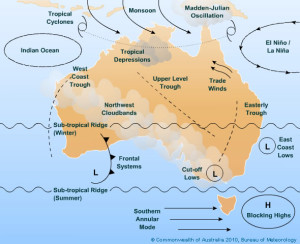

Weather and climate drivers: Floods, drought, and climate change are all driven by a number of processes in the atmosphere and oceans but the changes are driven at different timescales. The drivers shown in the map interact with each other and influence different parts of the continent to bring local weather and climate. The drivers include circulation patterns in the Pacific Ocean that bring El Niño conditions associated with drought in eastern Australia and La Niña conditions that are associated with floods. The Indian Ocean Dipole is a similar pattern in the Indian Ocean that can bring drought to south-west and south-east Australia, and the Southern Annular Mode are the major influences on rainfall (and thus runoff) in Australia. For more detail visit BOM here.

Relatively small changes in rainfall are amplified to much larger changes in runoff and groundwater recharge, which make Australia’s water resources the most variable in the world. Water management is highly adapted to this variability, but the millennium drought in south-east Australia and the sharp drop in runoff in the South West of Western Australia since 1975 have tested the effectiveness of these adaptations. New measures are being introduced such as urban water supplies that are less dependent on runoff and the return of water to the environment to make it more sustainable. Climate change is occurring on top of that variability and in southern Australia it is likely to further reduce water resources. For the moderate climate change predicted to occur by 2030, the adaptation to droughts and floods can be effective, because the worst consequences are likely to be more intense droughts and less frequent but more intense floods. For further climate change, projected to occur by 2050 or 2070, the conditions of the millennium drought might become the average future water availability, which would have profound consequences for the way water is used and for ecosystems. The understanding of how climate influences water can help make water management more adaptable, such as through improved seasonal forecasts, and it can help communities plan how they will respond to reduced water availability in future. Source: CSIRO Water 7 climate chapter 3 from Water – Science & Solutions Report

Understanding the ENSO Influence

Source: BOM ENSO Wrap-up

Groundwater use is increasing across Australia but the total use is difficult to estimate. Most groundwater is extracted by individual users and is rarely metered, and only a small fraction is managed through distribution networks. In 2004–05, licences for groundwater use were about 4700 GL/year, or 25% of the total amount of water consumed in Australia.2,3 Unlicensed use of groundwater – mainly for stock and domestic uses – is estimated to consume an additional 1100 GL/year.4 The amount of groundwater used is estimated to have almost doubled since the mid 1980s. Increased use of groundwater has been facilitated by recent drilling technologies and cheap submersible pumps that can lift water from considerable depths. In the drier parts of Australia, groundwater is the predominant water source because surface water resources are so scarce. Perth and Alice Springs, for example, rely on groundwater for about 80 and 100% of their water supply, respectively. When surface water resources become scarce, users turn to groundwater to meet their needs. Declines in surface water availability during the millennium drought in the southern Murray–Darling Basin led to a modest rise in groundwater use (1240 GL in 2000–01 to 1531 GL in 2007–08), but a sharp rise in the proportion of water supplied from groundwater (11% to 37%).5 Given the reliability of supply and convenience of self supply, the use of groundwater may not return to previous levels, even when surface water availability does.

Many aquifers with high historical rates of use are showing symptoms of over-use, such as falling water tables and lower aquifer pressures and subsequent impacts on future use, groundwater salinity, river flows, and ecosystems. The level of over-use was not recognised for decades because of the lags inherent in large, flat, and slow moving groundwater systems. Remediation of these systems is expensive and difficult because salinity and ecological damage are hard to reverse, and because of the historical expectation of reliable water supplies. Inadvertent impacts of recent strong growth in groundwater use have not been felt yet and, given that the consequences of present use are in many cases still to be felt, some caution should be exercised around future groundwater development, by putting effective risk assessment and management processes in place. Source: CSIRO Water & Climate chapter 4 from Water – Science & Solutions Report

All things groundwater in Australia

BOM Groundwater information: The Bureau provides a suite of nationally consistent groundwater data and information products. Government, industry and the general public can use these products to inform decision-making and research about groundwater resources.

Groundwater information products:

- Australian Groundwater Insight: Interpreted national and regional groundwater information Insight

- Australian Groundwater Explorer: Bore data visualisation, selection and download Explorer

- National Groundwater Information System: Spatial groundwater database for GIS specialists Information System

- Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems Atlas: National inventory of groundwater dependent ecosystems Atlas

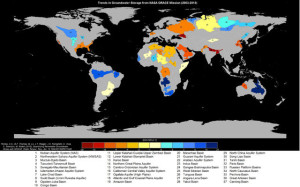

A third of the world’s biggest groundwater basins are in distress

16 June 2015, Two new studies led by UC Irvine using data from NASA Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellites show that civilization is rapidly draining some of its largest groundwater basins, yet there is little to no accurate data about how much water remains in them. The result is that significant segments of Earth’s population are consuming groundwater quickly without knowing when it might run out, the researchers conclude. The findings appear today in Water Resources Research. “Available physical and chemical measurements are simply insufficient,” said UCI professor and principal investigator Jay Famiglietti, who is also the senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left.”

The studies are the first to characterize groundwater losses via data from space, using readings generated by NASA’s twin GRACE satellites that measure dips and bumps in Earth’s gravity, which is affected by the weight of water. For the first paper, researchers examined the planet’s 37 largest aquifers between 2003 and 2013. The eight worst off were classified as overstressed, with nearly no natural replenishment to offset usage. Another five aquifers were found, in descending order, to be extremely or highly stressed, depending upon the level of replenishment in each — still in trouble but with some water flowing back into them. The most overburdened are in the world’s driest areas, which draw heavily on underground water. Climate change and population growth are expected to intensify the problem. Read More here

Need for Water Futures and Solutions

Agriculture – feeding the world

7 June 2016, YALE Connections: Climate Changing the Menu: A selection of downloadable reports on climate change, agriculture, and food. Along with the flood of books dealing with food and climate change issues, a wealth of free substantive reports, available as PDF downloads, also beckon for readers’ attention and action. Part Two of bibliophile Michael Svoboda’s “Climate changing the menu” selections offers links to a trove of recent authoritative reports . . . enough to make any foodie late for their next meal. The descriptions of the studies below are drawn from copy provided by the publishers. Access reports here

In 2009 seven countries (USA, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Russia and France) were responsible for more than 50% of the annual global exports of wheat, maize, soybeans, rapeseed, chicken and beef. In addition, two countries (Thailand and Vietnam) were responsible for 50% of the annually export of rice. Most of these exporting countries have access to significant amounts of annually renewable water resources, Australia being the exception. This chapter also shows how the amount of virtual water differs between the different countries. Source: Virtual Water, University of British Columbia

Australia and the Global Food and Water Crisis

Source: Water Scarcity and Future Challenges for Food Production

Future Directions International preamble from their webpage regarding “Australia’s role in solving future global food and water crises”: Food and water insecurity are among the most formidable challenges facing the world. The potential for food or water crises to manifest between now and 2050 is high. If such events were to occur, they would lead to rising poverty levels, slowing growth and development, and widespread instability and conflict. Australia’s greatest responsibility and opportunity in the 21st century is to help feed a hungry world. Mobilisation of political will and an overhaul of the existing global food systems are critical to avert crises. To access Future Directions Reports: “Food and Water Security: Our Global Challenge”; The Forgotten Resource: Groundwater in Australia

28 May 2015, Future Directions International: Urban agriculture is becoming an increasingly prominent topic in discussions on food security in Australia. More than 90 per cent of Australia’s population lives in urban centres and depends on a decreasing agricultural workforce to meet increasing food demand. Long food supply chains, although economically efficient, lead to poor nutritional and environmental outcomes for society. The re-localisation of food production will support and enhance Australia’s food system and has the potential to increase access to nutritious, affordable food for the most vulnerable.

Australia produces enough food to feed 60 million people, yet economic barriers leave an estimated 2 million Australians dependent on food relief annually. Foodbank Australia is reportedly struggling to meet demand; it turns away as many as 60,000 people each month due to a shortage of food. To enhance food security, efforts need to be focussed on overcoming the increasingly volatile food prices that are expected to occur as a result of increased production and energy costs and the effects of climate change.

There is a strong consensus amongst academics and policy makers that urban agriculture is a viable means of increasing domestic food security. Urban agriculture has assisted communities in both developed and developing nations to cope with food insecurity, by ensuring local availability of nutritional and affordable food. Greater support, however, is required from the Federal, State and Local governments, to ensure that benefits can be realised within Australian cities. Read More here

Complexity of food distribution

March 2015, NASA GISS Science Brief, Study Assesses Fragility of Global Food System: If you were in the New York metropolitan area (the home of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies) in the days after Hurricane Sandy, you might have experienced something seemingly unthinkable in 21st century America: empty food shelves at the supermarkets for days and days. New Yorkers believe that they can stand up to whatever life throws at them, yet this experience caught even the proudest natives off-guard…..Taking a step back, should we really be surprised by a disruption to our regional food system? More importantly, how concerned should we be about the stability of our global food system in a world marked by geopolitical, economic, and climatic uncertainties? Read More here

March 2015, NASA GISS Science Brief, Study Assesses Fragility of Global Food System: If you were in the New York metropolitan area (the home of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies) in the days after Hurricane Sandy, you might have experienced something seemingly unthinkable in 21st century America: empty food shelves at the supermarkets for days and days. New Yorkers believe that they can stand up to whatever life throws at them, yet this experience caught even the proudest natives off-guard…..Taking a step back, should we really be surprised by a disruption to our regional food system? More importantly, how concerned should we be about the stability of our global food system in a world marked by geopolitical, economic, and climatic uncertainties? Read More here

Zero Carbon Australia Discussion Paper: Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry: Emissions in the agriculture and forestry sectors in Australia are high and growing. The UNFCCC National Inventory Report suggests that sources of land use emissions, such as land clearing for agriculture and enteric (intestinal) fermentation from digestive processes in livestock, contribute 15% of national emissions. Australia’s land use sector is in a unique position to mitigate (reduce) climate impacts and take a leading role in addressing climate change. Agriculture and forestry are the only sectors of the Australian economy that can draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by sequestering it in growing plants and in the soil. The agriculture and forestry sectors can mitigate climate impacts on the land, bringing prosperity to rural areas in the process. The Zero Carbon Australia Land Use report explores how this can be done.

Zero Carbon Australia Discussion Paper: Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry: Emissions in the agriculture and forestry sectors in Australia are high and growing. The UNFCCC National Inventory Report suggests that sources of land use emissions, such as land clearing for agriculture and enteric (intestinal) fermentation from digestive processes in livestock, contribute 15% of national emissions. Australia’s land use sector is in a unique position to mitigate (reduce) climate impacts and take a leading role in addressing climate change. Agriculture and forestry are the only sectors of the Australian economy that can draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by sequestering it in growing plants and in the soil. The agriculture and forestry sectors can mitigate climate impacts on the land, bringing prosperity to rural areas in the process. The Zero Carbon Australia Land Use report explores how this can be done.

The ZCA Land Use Report outlines a range of measures that can substantially reduce emissions and provide opportunities for farmers in building resilience to the impacts of climate change. These measures encompass both agriculture and forestry and address emissions at the scale required to prevent catastrophic climate change. The Land Use Report analyses the suite of land use practices in Australia for their function as a source of greenhouse emissions, the potential of the landscape to draw down atmospheric CO2, and the likely impact of changes to land use patterns on local economies. The report provides a comprehensive assessment of how Australia can manage its productive capacity, ecological heritage and ecosystems services for the future. The ZCA Land Use report is can be ordered via our online shop. It is also available for free download.