What you will find on this page: how climate change shapes food insecurity (video); Weather Alert: 4 Corners program (video); About time we got over the “yuk” factor for recycled water (video); Farmers for Climate Action (video); Cool Farm Tool online calulator; Australia’s future food security; WRI Challenge; UNEP summary; BOM water sites: Australia’s water challenge; climate drivers; understanding ENSO (video); groundwater use; water futures; water trading; agriculture; food & water crisis; localising food production; complex food distribution; land use – agriculture & forestry; latest news; also refer to page “impacts observed & projected” as the issues are closely related

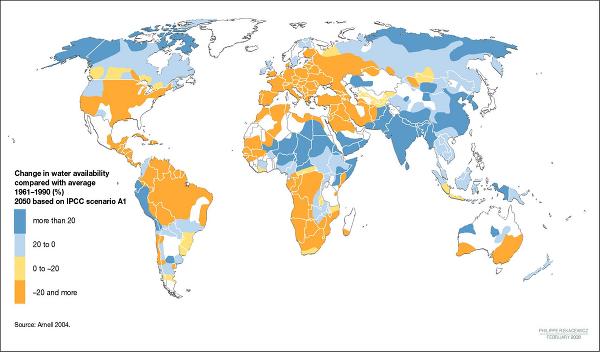

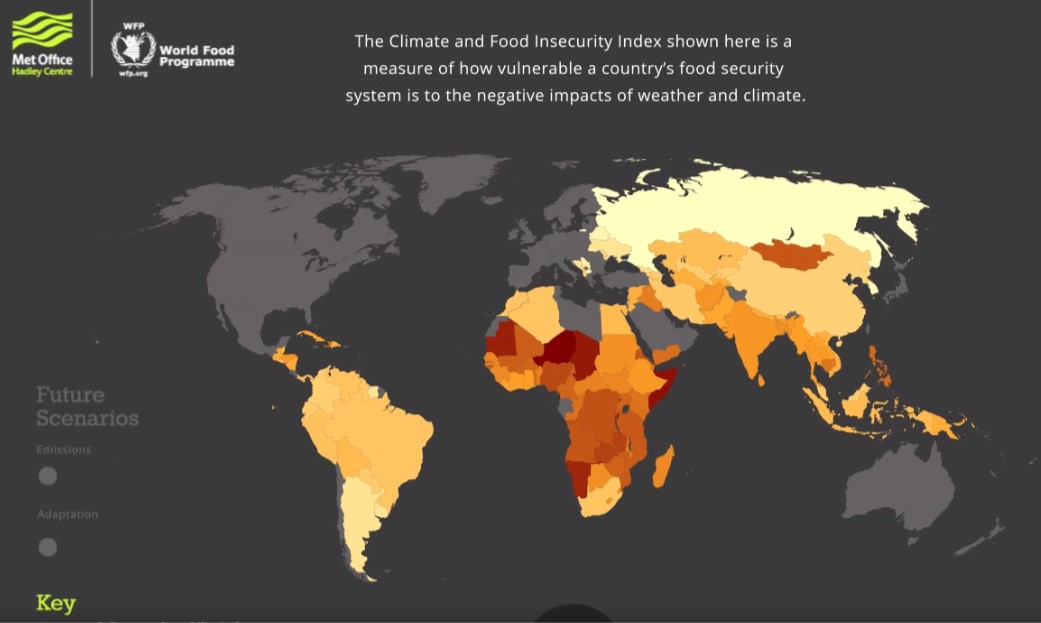

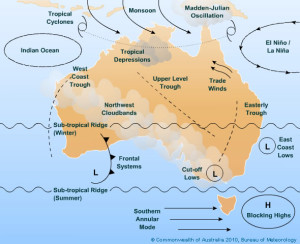

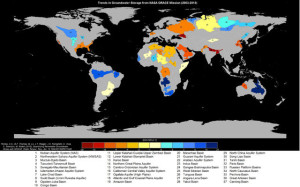

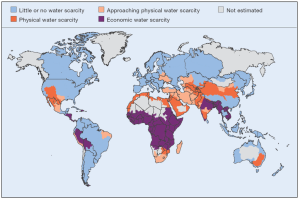

Latest News 16 October 2025, The conversation: The climate crisis is fuelling extreme fires across the planet. We’ve all seen the alarming images. Smoke belching from the thick forests of the Amazon. Spanish firefighters battling flames across farmland. Blackened celebrity homes in Los Angeles and smoked out regional towns in Australia. If you felt like wildfires and their impacts were more extreme in the past year – you’re right. Our new report, a collaboration between scientists across continents, shows climate change supercharged the world’s wildfires in unpredictable and devastating ways. Human-caused climate change increased the area burned by wildfires, called bushfires in Australia, by a magnitude of 30 in some regions in the world. Our snapshot offers important new evidence of how climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme fires. And it serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions. The evidence is clear – climate change is making fires worse… In the past year, a land area larger than India – about 3.7 million square kilometres – was burnt globally. More than 100 million people were affected by these fires, and US$215 billion worth of homes and infrastructure were at risk. In Australia, bushfires did not reach the overall extent or impact of previous seasons, such as the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. Nonetheless, more than 1,000 large fires burned around 470,000 hectares in Western Australia, and more than 5 million hectares burned in central Australia. In Victoria, the Grampians National Park saw two-thirds of its area burned. Read more here 16 October 2025, The Conversation: A crucial store of carbon in Australia’s tropical forests has switched from carbon sink to carbon source. One approach to help fight climate change is to protect natural forests, as they absorb some atmospheric carbon released by burning fossil fuels and store large volumes of carbon. Our new research on Australia’s tropical rainforests challenges the assumption that they will keep absorbing more carbon than they release. We found that as climate change has intensified over the past half-century, less and less carbon has been taken up and converted to wood in the stems and branches of the trees in these forests. Woody biomass is a large and relatively stable store of carbon in forests, and acts as an important indicator of overall forest health. The effect has been so pronounced that the woody biomass of these forests has gone from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. This means carbon is being lost to the atmosphere due to trees dying faster than it is being replaced by tree growth. This is the first time woody biomass in tropical forests has been shown to switch from sink to source. Our research indicates the shift likely happened about 25 years ago. It remains to be seen whether Australian tropical forests are a harbinger for other tropical forests globally. Read more here 7 October 2025, Insurance Council of Australia: Extreme weather costs: the silver medal we don’t want. New data released by the Insurance Council of Australia (ICA) today shows that Australia has consistently taken the silver medal for extreme weather losses over the last 45 years – beaten only by the United States. The data uses both the insured and broader economic costs of extreme weather, averaged across the populations of each of six developed countries in order to accurately compare the growing impact of extreme weather. Published as part of the ICA’s annual 2024-25 Insurance Catastrophe Resilience Report, the data from Munich Re’s NatCatSERVICE global database shows that for most of the last 45 years Australia has ranked second only behind the United States for economic and insured losses per capita – and was only pushed into third place in the last five years by two extraordinary events in New Zealand. Each decade since 1980, inflation-adjusted losses from floods, bushfires, storms and extreme cold temperatures have climbed across the globe, with the Report looking at France, Canada, and Germany in addition to Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Australia’s persistent second place reflects our unique geography and exposure to natural perils, compounded by the growth of populations in higher-risk areas and infrastructure that has not been built to withstand the impacts of a changing climate. Also included in the Report is updated data on the cost of extreme weather over the past 12 months, with insured losses reaching almost $2 billion across three events – the North Queensland Floods ($289m), Ex-Tropical Cyclone Alfred ($1.43b), and the Mid North Coast and Hunter floods ($248m). Read more here 7 October 2025, The Conversation: Extreme weather now costs Australians $4.5b a year. Better insurance options and loans would help us adapt. Today’s release of the Insurance Council of Australia’s report puts Australia on the spot: we rank second in the world in extreme weather-related losses. As the Insurance Council puts it, this is not the silver medal we want to win. Why is this a problem? According to the Resilient Building Council of Australia, a collaboration of independent experts, close to 90% of Australian homes are not actually fit for a changing climate. Many renters, low income groups, and people living in high-risk areas are especially vulnerable and often unable to even get insurance. In the 2020s, Australia has spent around A$4.5 billion a year on extreme weather costs, while insurance affordability and access are plummeting in regions that need it the most. The report found almost eight in ten of the homes that face severe to extreme flood risk do not have flood insurance. Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment, released last month, predicted a staggering 444% increase in heat-related deaths in Sydney as heatwaves become more severe under the most extreme scenario of 3°C degree warming by 2050. Other very dire numbers are outlined for climate risks across the country. The insurance industry says we need to rethink how we can keep our communities safe and thriving in the face of escalating disasters. How do we make sure these safety nets actually work for people – especially when costs and losses are escalating? Read More Here End Latest News Interactive: How climate change shapes food insecurity across the world 1 December 2015, Carbon Brief: Rising temperatures and more extreme weather are set to increase the pressure on food supplies around the world, risking shortages in the least-developed and developing countries and potentially pushing millions of people into deeper hunger and malnutrition. This is the message from the Met Office and the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), who have joined forces to launch a new interactive map at the COP21 conference underway in Paris. The graphic lets you see where in the world is already vulnerable to food ‘shocks’, and how the picture changes depending on how much action, if any, we take to reduce our emissions. Click on image to open video Drinking recycled water (or as this video calls it, poop water) isn’t the most appealing notion for many people. But it’s becoming increasingly necessary––this video digs into some of the ways people have come to accept it. Source: Holly Kaw! Do we drink recycled water in Australia? Depending on where you live, or where you’ve travelled, there’s a chance you’ve already drunk recycled water. Water recycling happens in other regions of Australia but the water is generally directed exclusively for irrigation or industrial use. Recycled water overseas FCA is an alliance of farmers and leaders in agriculture who are working with their peers, the wider sector and decision-makers to make sure Australia takes the actions necessary to address damage to our climate. FCA is determined to see farmers and agriculture get the support and investment it needs to adapt to a changing climate, as well as be part of the solution. Members are spread far and wide across the country: from the tropical north of Queensland to Tasmania, and from the wine growing regions of Western Australia right across to the sheep and cropping farms of New South Wales. Farmers for Climate Action is an associate member of the National Farmers Federation, and a member of the Climate Action Network Australia (CANA). We work closely with stakeholders within the agricultural and climate realms. Learn more about Farmers for Climate Action here Feeding a Hungry Nation: Climate change, food and farming in Australia Climate change is affecting the quality and seasonal availability of many foods in Australia. Australia is extremely vulnerable to disruptions in food supply through extreme weather events. Climate change is the most challenging threat to food and water security between now and 2050 Water risks like stress and variable supply threaten everything from agriculture to industry to energy production. Already, 69 countries and one-quarter of the world’s cropland face high water stress. These challenges will likely become more severe as competition for water increases and climate change shifts precipitation patterns. The World Economic Forum identified global water crises as one of the top five global risks for businesses. Without tools to evaluate these risks and inform management plans, businesses’ bottom lines will suffer. Read More here UNEP: The real concern for the future, in the context of changing patterns of rainfall, is the decrease of run-off water which may put at risk large areas of arable land. The map shows how seriously this issue must be taken, while the forecast indicates that some of the richest arable regions (Europe, United States, parts of Brazil, southern Africa) are threatened with a significant reduction of run-off water, resulting in a lack of water for rain-fed agriculture and thus putting millions at risks. The accelerating changes in our global climate will undoubtedly cause major changes in the patterns of water cycle and geographical distribution, in the near future. Some regions will receive less precipitation, some more, and this will significantly affect agricultural activity. While some regions will see a reduction in arable land, others will have more suitable land for agriculture. It’s likely that certain types of agriculture will migrate and traditional areas for crops will change. In other words, climate change will alter the geography of traditional crop areas, which may impact on the world’s capacity to provide enough food for all. Since the 1990s, the scientific community has been warning about the rapidly changing climate, endeavouring to convince people to take urgent measures to mitigate the changes. These multiple warnings have been ignored until very recently, but the issue is now a priority with many international organizations. However, all reliable climate scenarios run by the IPCC and published in the fourth assessment reports show the following results: In other words, ongoing climate change will mean that the water supply for human communities will become more and more uncertain. The IPCC has stated that between 2000 and 2005 in the northern hemisphere, climate change accelerated faster than predicted, with the consequence that the water cycle could change in an unpredictable way, leading to the possibility of increases in extreme weather. The fear is that with all these changes, even if the quantity of water in the world does not change, the level of accessibility of the theoretically available water may significantly change. Source: UNEP Future Directions International highlights Australia’s challenge BOM water information and update sites 3 August 2015, The Conversation, The role of water in Australia’s uncertain future: If you live in an Australian city, there’s a good chance that your water comes from surface water such as streams, rivers and reservoirs filled by rainfall and runoff. If you live in Perth, much of your water (about 40%) comes from groundwater. But you might be surprised to know that a sizeable proportion of water in Australia came from recycling or desalination in 2013-14. 39% of Perth’s water came from desalination and 41% of Adelaide’s. All cities also used small portions of recycled water: Melbourne (4%), Sydney (7%), southeast Queensland (7%), and Canberra (8%). The Bureau of Meteorology recently released, for the first time, comprehensive national data on these “climate-resilient” water sources, through a new online portal provided as part of the Bureau’s Improving Water Information program. Climate-resilient water sources are those on which climate variability, such as variations in rainfall, temperature and drought, has little or no influence. The data set provides information on two of the most significant such sources: desalination and water recycling. The Climate Resilient Water Sources web portal is an interactive site providing comprehensive mapping and information of desalinated and recycled water sources for over 350 sites across Australia, both publicly and privately owned and operated. Users can access the portal, to search information on capacity, production, location and use of these alternative water sources across Australia. How many desalination and recycled water plants does Australia have? Below you can see the amount of desalinated and recycled water sourced for Australia’s cities in 2013–14 from the National Performance Report released in May 2015. From the Climate Resilient Water Source data we can also see which parts of Australia have the greatest climate resilient capacity compared to their sourced water (including surface, ground, recycled water and desalination). Western Australia has greater climate resilient capacity than its total water sourced in 2013–14, as you can see in the chart below: We can also see that more than 50% of reported production of recycled or desalinated water in 2012-13 (410,491 ML) was for urban use (residential, domestic, commercial, industrial, municipal). Read More here Improving Water Information: data, status and forecasts Australia’s variable climate drivers Weather and climate drivers: Floods, drought, and climate change are all driven by a number of processes in the atmosphere and oceans but the changes are driven at different timescales. The drivers shown in the map interact with each other and influence different parts of the continent to bring local weather and climate. The drivers include circulation patterns in the Pacific Ocean that bring El Niño conditions associated with drought in eastern Australia and La Niña conditions that are associated with floods. The Indian Ocean Dipole is a similar pattern in the Indian Ocean that can bring drought to south-west and south-east Australia, and the Southern Annular Mode are the major influences on rainfall (and thus runoff) in Australia. For more detail visit BOM here. Relatively small changes in rainfall are amplified to much larger changes in runoff and groundwater recharge, which make Australia’s water resources the most variable in the world. Water management is highly adapted to this variability, but the millennium drought in south-east Australia and the sharp drop in runoff in the South West of Western Australia since 1975 have tested the effectiveness of these adaptations. New measures are being introduced such as urban water supplies that are less dependent on runoff and the return of water to the environment to make it more sustainable. Climate change is occurring on top of that variability and in southern Australia it is likely to further reduce water resources. For the moderate climate change predicted to occur by 2030, the adaptation to droughts and floods can be effective, because the worst consequences are likely to be more intense droughts and less frequent but more intense floods. For further climate change, projected to occur by 2050 or 2070, the conditions of the millennium drought might become the average future water availability, which would have profound consequences for the way water is used and for ecosystems. The understanding of how climate influences water can help make water management more adaptable, such as through improved seasonal forecasts, and it can help communities plan how they will respond to reduced water availability in future. Source: CSIRO Water 7 climate chapter 3 from Water – Science & Solutions Report Understanding the ENSO Influence Source: BOM ENSO Wrap-up Groundwater use is increasing across Australia but the total use is difficult to estimate. Most groundwater is extracted by individual users and is rarely metered, and only a small fraction is managed through distribution networks. In 2004–05, licences for groundwater use were about 4700 GL/year, or 25% of the total amount of water consumed in Australia.2,3 Unlicensed use of groundwater – mainly for stock and domestic uses – is estimated to consume an additional 1100 GL/year.4 The amount of groundwater used is estimated to have almost doubled since the mid 1980s. Increased use of groundwater has been facilitated by recent drilling technologies and cheap submersible pumps that can lift water from considerable depths. In the drier parts of Australia, groundwater is the predominant water source because surface water resources are so scarce. Perth and Alice Springs, for example, rely on groundwater for about 80 and 100% of their water supply, respectively. When surface water resources become scarce, users turn to groundwater to meet their needs. Declines in surface water availability during the millennium drought in the southern Murray–Darling Basin led to a modest rise in groundwater use (1240 GL in 2000–01 to 1531 GL in 2007–08), but a sharp rise in the proportion of water supplied from groundwater (11% to 37%).5 Given the reliability of supply and convenience of self supply, the use of groundwater may not return to previous levels, even when surface water availability does. Many aquifers with high historical rates of use are showing symptoms of over-use, such as falling water tables and lower aquifer pressures and subsequent impacts on future use, groundwater salinity, river flows, and ecosystems. The level of over-use was not recognised for decades because of the lags inherent in large, flat, and slow moving groundwater systems. Remediation of these systems is expensive and difficult because salinity and ecological damage are hard to reverse, and because of the historical expectation of reliable water supplies. Inadvertent impacts of recent strong growth in groundwater use have not been felt yet and, given that the consequences of present use are in many cases still to be felt, some caution should be exercised around future groundwater development, by putting effective risk assessment and management processes in place. Source: CSIRO Water & Climate chapter 4 from Water – Science & Solutions Report All things groundwater in Australia BOM Groundwater information: The Bureau provides a suite of nationally consistent groundwater data and information products. Government, industry and the general public can use these products to inform decision-making and research about groundwater resources. Groundwater information products: A third of the world’s biggest groundwater basins are in distress 16 June 2015, Two new studies led by UC Irvine using data from NASA Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellites show that civilization is rapidly draining some of its largest groundwater basins, yet there is little to no accurate data about how much water remains in them. The result is that significant segments of Earth’s population are consuming groundwater quickly without knowing when it might run out, the researchers conclude. The findings appear today in Water Resources Research. “Available physical and chemical measurements are simply insufficient,” said UCI professor and principal investigator Jay Famiglietti, who is also the senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left.” The studies are the first to characterize groundwater losses via data from space, using readings generated by NASA’s twin GRACE satellites that measure dips and bumps in Earth’s gravity, which is affected by the weight of water. For the first paper, researchers examined the planet’s 37 largest aquifers between 2003 and 2013. The eight worst off were classified as overstressed, with nearly no natural replenishment to offset usage. Another five aquifers were found, in descending order, to be extremely or highly stressed, depending upon the level of replenishment in each — still in trouble but with some water flowing back into them. The most overburdened are in the world’s driest areas, which draw heavily on underground water. Climate change and population growth are expected to intensify the problem. Read More here Need for Water Futures and Solutions 7 June 2016, YALE Connections: Climate Changing the Menu: A selection of downloadable reports on climate change, agriculture, and food. Along with the flood of books dealing with food and climate change issues, a wealth of free substantive reports, available as PDF downloads, also beckon for readers’ attention and action. Part Two of bibliophile Michael Svoboda’s “Climate changing the menu” selections offers links to a trove of recent authoritative reports . . . enough to make any foodie late for their next meal. The descriptions of the studies below are drawn from copy provided by the publishers. Access reports here In 2009 seven countries (USA, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Russia and France) were responsible for more than 50% of the annual global exports of wheat, maize, soybeans, rapeseed, chicken and beef. In addition, two countries (Thailand and Vietnam) were responsible for 50% of the annually export of rice. Most of these exporting countries have access to significant amounts of annually renewable water resources, Australia being the exception. This chapter also shows how the amount of virtual water differs between the different countries. Source: Virtual Water, University of British Columbia Australia and the Global Food and Water Crisis Source: Water Scarcity and Future Challenges for Food Production Future Directions International preamble from their webpage regarding “Australia’s role in solving future global food and water crises”: Food and water insecurity are among the most formidable challenges facing the world. The potential for food or water crises to manifest between now and 2050 is high. If such events were to occur, they would lead to rising poverty levels, slowing growth and development, and widespread instability and conflict. Australia’s greatest responsibility and opportunity in the 21st century is to help feed a hungry world. Mobilisation of political will and an overhaul of the existing global food systems are critical to avert crises. To access Future Directions Reports: “Food and Water Security: Our Global Challenge”; The Forgotten Resource: Groundwater in Australia 28 May 2015, Future Directions International: Urban agriculture is becoming an increasingly prominent topic in discussions on food security in Australia. More than 90 per cent of Australia’s population lives in urban centres and depends on a decreasing agricultural workforce to meet increasing food demand. Long food supply chains, although economically efficient, lead to poor nutritional and environmental outcomes for society. The re-localisation of food production will support and enhance Australia’s food system and has the potential to increase access to nutritious, affordable food for the most vulnerable. Australia produces enough food to feed 60 million people, yet economic barriers leave an estimated 2 million Australians dependent on food relief annually. Foodbank Australia is reportedly struggling to meet demand; it turns away as many as 60,000 people each month due to a shortage of food. To enhance food security, efforts need to be focussed on overcoming the increasingly volatile food prices that are expected to occur as a result of increased production and energy costs and the effects of climate change. There is a strong consensus amongst academics and policy makers that urban agriculture is a viable means of increasing domestic food security. Urban agriculture has assisted communities in both developed and developing nations to cope with food insecurity, by ensuring local availability of nutritional and affordable food. Greater support, however, is required from the Federal, State and Local governments, to ensure that benefits can be realised within Australian cities. Read More here

Complexity of food distribution The ZCA Land Use Report outlines a range of measures that can substantially reduce emissions and provide opportunities for farmers in building resilience to the impacts of climate change. These measures encompass both agriculture and forestry and address emissions at the scale required to prevent catastrophic climate change. The Land Use Report analyses the suite of land use practices in Australia for their function as a source of greenhouse emissions, the potential of the landscape to draw down atmospheric CO2, and the likely impact of changes to land use patterns on local economies. The report provides a comprehensive assessment of how Australia can manage its productive capacity, ecological heritage and ecosystems services for the future. The ZCA Land Use report is can be ordered via our online shop. It is also available for free download. Water and climate change

7 October 2015, Climate Council: The price, quality and seasonality of Australia’s food is increasingly being affected by climate change with Australia’s future food security under threat, our new report has revealed. Australia’s food supply chain is highly exposed to disruption from increasing extreme weather events driven by climate change, with farmers already struggling to cope with more frequent and intense droughts and changing weather patterns.

7 October 2015, Climate Council: The price, quality and seasonality of Australia’s food is increasingly being affected by climate change with Australia’s future food security under threat, our new report has revealed. Australia’s food supply chain is highly exposed to disruption from increasing extreme weather events driven by climate change, with farmers already struggling to cope with more frequent and intense droughts and changing weather patterns.

Agriculture – feeding the world

March 2015, NASA GISS Science Brief, Study Assesses Fragility of Global Food System: If you were in the New York metropolitan area (the home of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies) in the days after Hurricane Sandy, you might have experienced something seemingly unthinkable in 21st century America: empty food shelves at the supermarkets for days and days. New Yorkers believe that they can stand up to whatever life throws at them, yet this experience caught even the proudest natives off-guard…..Taking a step back, should we really be surprised by a disruption to our regional food system? More importantly, how concerned should we be about the stability of our global food system in a world marked by geopolitical, economic, and climatic uncertainties? Read More here

March 2015, NASA GISS Science Brief, Study Assesses Fragility of Global Food System: If you were in the New York metropolitan area (the home of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies) in the days after Hurricane Sandy, you might have experienced something seemingly unthinkable in 21st century America: empty food shelves at the supermarkets for days and days. New Yorkers believe that they can stand up to whatever life throws at them, yet this experience caught even the proudest natives off-guard…..Taking a step back, should we really be surprised by a disruption to our regional food system? More importantly, how concerned should we be about the stability of our global food system in a world marked by geopolitical, economic, and climatic uncertainties? Read More here Zero Carbon Australia Discussion Paper: Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry: Emissions in the agriculture and forestry sectors in Australia are high and growing. The UNFCCC National Inventory Report suggests that sources of land use emissions, such as land clearing for agriculture and enteric (intestinal) fermentation from digestive processes in livestock, contribute 15% of national emissions. Australia’s land use sector is in a unique position to mitigate (reduce) climate impacts and take a leading role in addressing climate change. Agriculture and forestry are the only sectors of the Australian economy that can draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by sequestering it in growing plants and in the soil. The agriculture and forestry sectors can mitigate climate impacts on the land, bringing prosperity to rural areas in the process. The Zero Carbon Australia Land Use report explores how this can be done.

Zero Carbon Australia Discussion Paper: Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry: Emissions in the agriculture and forestry sectors in Australia are high and growing. The UNFCCC National Inventory Report suggests that sources of land use emissions, such as land clearing for agriculture and enteric (intestinal) fermentation from digestive processes in livestock, contribute 15% of national emissions. Australia’s land use sector is in a unique position to mitigate (reduce) climate impacts and take a leading role in addressing climate change. Agriculture and forestry are the only sectors of the Australian economy that can draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by sequestering it in growing plants and in the soil. The agriculture and forestry sectors can mitigate climate impacts on the land, bringing prosperity to rural areas in the process. The Zero Carbon Australia Land Use report explores how this can be done.