What you will find on this page: LATEST NEWS; we are the asteroid (video); worldwide tree cover loss/gain; (interactive map) impacts & adaptation NRM regions; knowing what to protect; management & planning; climate zones on the move; invasive species; examples of ecosystem impacts; latest news; information & resource sites; also refer to pages “impacts observed & projected” and” population & consumption” as the issues are closely related

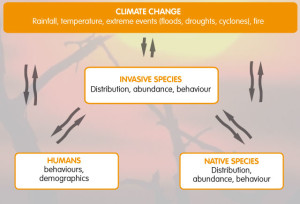

Latest News 16 October 2025, The conversation: The climate crisis is fuelling extreme fires across the planet. We’ve all seen the alarming images. Smoke belching from the thick forests of the Amazon. Spanish firefighters battling flames across farmland. Blackened celebrity homes in Los Angeles and smoked out regional towns in Australia. If you felt like wildfires and their impacts were more extreme in the past year – you’re right. Our new report, a collaboration between scientists across continents, shows climate change supercharged the world’s wildfires in unpredictable and devastating ways. Human-caused climate change increased the area burned by wildfires, called bushfires in Australia, by a magnitude of 30 in some regions in the world. Our snapshot offers important new evidence of how climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme fires. And it serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions. The evidence is clear – climate change is making fires worse… In the past year, a land area larger than India – about 3.7 million square kilometres – was burnt globally. More than 100 million people were affected by these fires, and US$215 billion worth of homes and infrastructure were at risk. In Australia, bushfires did not reach the overall extent or impact of previous seasons, such as the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. Nonetheless, more than 1,000 large fires burned around 470,000 hectares in Western Australia, and more than 5 million hectares burned in central Australia. In Victoria, the Grampians National Park saw two-thirds of its area burned. Read more here 16 October 2025, The Conversation: A crucial store of carbon in Australia’s tropical forests has switched from carbon sink to carbon source. One approach to help fight climate change is to protect natural forests, as they absorb some atmospheric carbon released by burning fossil fuels and store large volumes of carbon. Our new research on Australia’s tropical rainforests challenges the assumption that they will keep absorbing more carbon than they release. We found that as climate change has intensified over the past half-century, less and less carbon has been taken up and converted to wood in the stems and branches of the trees in these forests. Woody biomass is a large and relatively stable store of carbon in forests, and acts as an important indicator of overall forest health. The effect has been so pronounced that the woody biomass of these forests has gone from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. This means carbon is being lost to the atmosphere due to trees dying faster than it is being replaced by tree growth. This is the first time woody biomass in tropical forests has been shown to switch from sink to source. Our research indicates the shift likely happened about 25 years ago. It remains to be seen whether Australian tropical forests are a harbinger for other tropical forests globally. Read more here 30 September 2025, The Conversation: Air temperatures over Antarctica have soared 35ºC above average. What does this unusual event mean for Australia? Right now, cold air high above Antarctica is up to 35ºC warmer than normal. Normally, strong winds and the lack of sun would keep the temperature at around –55°C. But it’s risen sharply to around –20°C. The sudden heating began in early September and is still taking place. Three separate pulses of heat have each pushed temperatures up by 25ºC or more. Temperatures spiked and fell back and spiked again. It looks as if an unusual event known as sudden stratospheric warming is taking place – the unexpected warming of the stratosphere, 12 to 40 kilometres above ground. In the middle of an Antarctic winter, this atmospheric layer is normally exceptionally cold, averaging around –80°C. By the end of September it would be roughly –50ºC. This month, atmospheric waves carrying heat from the surface have pushed up into this layer. In the Northern Hemisphere, these events are very common, occurring once every two years. But in the south, sudden large-scale warming was long thought to be extremely rare. My research has shown they are more common than expected, if we group the very strong 2002 event with slightly weaker events such as in 2019 and 2024. Sudden warming may sound ominous. But weather is messy. Many factors play into what happens down where we live. Read more Here 13 June 2025, The Conversation: As Antarctic sea ice shrinks, iconic emperor penguins are in more peril than we thought. When winter comes to Antarctica, seals and Adélie penguins leave the freezing shores and head for the edge of the forming sea ice. But emperor penguins stay put. The existence of emperor penguins seems all but impossible. Their lives revolve around seasons, timing and access to “fast ice” – sea ice connected to the Antarctic coast. Here, the sea ice persists long enough into summer for the penguins to rear their chicks successfully. But climate change is upending the penguins’ carefully tuned biological cycles. The crucial sea ice they depend on is melting too early, plunging the chicks from some colonies into the sea before they are fully fledged. In the latest bad news for these penguins, research by the British Antarctic Survey examined satellite images from 2009 to 2024 to assess fast-ice conditions at 16 emperor penguin colonies south of South America. They noted an average 22% fall in numbers across these colonies. That translates to a decrease of 1.6% every year. This rate of loss is staggering. As the paper’s lead author Peter Fretwell told the ABC, the rate is about 50% worse than even the most pessimistic estimates. Read more here End Latest News Scientists’ Heighten Concerns About Global Extinctions 5 August 2015, Monthly Yale Climate Connections video (above) explores scientists’ concerns over pace and extent of species extinctions. One sentiment expressed: ‘We are the asteroid.’ The global rate of extinctions, “already very large,” is “ramping up” . . . with climate change helping bring about that “acceleration,” scientist James White of the University of Colorado cautions in this month’s “This is not Cool” Yale Climate Connections video. White’s concerns over extinctions are echoed by scientists James Hansen of Columbia University, Eric Rignot of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Gerardo Ceballos of the National University of Mexico, Jonathan Payne of Stanford University, Lee Kump of Penn State University, and Stephanie Kitkiewicz of MIT. Read More here CSIRO concludes: Climate change will impact Australia’s biodiversity conservation and protected areas: There is compelling evidence, gathered over past decades, that the impacts of climate change on the world’s biodiversity are likely to be significant. Protected areas (13.4 per cent of the country*) are crucial for conserving biodiversity and supporting ecological processes beneficial to human well-being. However, in most cases, planning and management frameworks for protected areas have historically been developed with little consideration future global climate change. Global Forest Watch: Forest monitoring designed for action. Global Forest Watch offers the latest data, technology and tools that empower people everywhere to better protect forests. Explore interactive charts and maps that summarize key statistics about global forests. Statistics and global rankings – including rates of forest change, forest extent and drivers of deforestation – can be customized, easily shared and downloaded for offline use. Download global statistics by country here. Across Australia research has been conducted to develop a deeper understanding of how climate change will impact upon the country’s unique and diverse natural resources and natural resource management (NRM) activities. Click on the map to explore what adaptation research has been conducted to support natural resource managers to plan for and consider the impact of climate change for Australia’s regions. In these pages (arranged by clusters) you will access background information on the region, key messages about the impact of climate change, and reports and other relevant supporting material. (Ballarat is situated at the top of the Southern Slopes NRM region) CSIRO: Making Australia’s biodiversity information accessible: Effective biodiversity research and management rely on comprehensive information about the species or ecosystems of interest. Without this information it is very difficult to obtain reliable results or make sound decisions. A major barrier to Australia’s biodiversity research and management efforts has been the fragmentation and inaccessibility of biodiversity data. Data and information on Australian species has traditionally been housed in museums, herbaria, universities, and government departments and organisations. Obtaining records and data sets from these groups involved considerable time and effort, and often resulted in incomplete information. To overcome these issues, Australia’s biodiversity information needed to be brought together and made easily available in the one place. Building a collaborative tool for sharing and analysing Australia’s biodiversity information: A collaboration between CSIRO, Australia’s museums and herbaria, universities, and the Australian Government established the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA); a national project focused on making biodiversity information accessible and usable. The ALA is funded by the Australian Government through the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS). Since 2010, the ALA team has worked to aggregate Australia’s biodiversity information and make it available online via the ALA website . Founded on the principle of data sharing – collect it once, share it, use it many times – the ALA provides free, online access to more than 50 million occurrence records1, based on specimens from natural history collections, field observations and surveys. These records are enriched by additional information including molecular data, photographs, maps, sound recordings and literature. The Climate Change in Australia website provides easy access to the projections information and data.The website houses 14 interactive tools for exploring data; a data download facility; a technical report describing the data sources, methods, observed changes and projections; reports and brochures that summarise the results for eight regions of Australia; a brochure on Data Delivery; a brochure on projections for selected cities; a Climate Campus for learning more about climate science and using projections in impact assessments; an online training course; and other resources for decision makers and communicators. Observed changes will continue into the future: Temperature projections for Australia from three different greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions scenarios. Research has shown that most of the changes observed over recent decades will continue into the future. Projections suggest that for Australia: CSIRO/NCCARF GUIDE: Implications of Climate Change for Biodiversity: A community-level modelling approach: Evidence over the last decade has shown that ecological change in response to climate change is unavoidable and will be widespread and substantial. Our ability to manage biodiversity through these changes depends on understanding what the nature of the change might be and where the potential for future persistence of biodiversity may be greatest. The scope of the challenge of adapting biodiversity management to climate change is shaped by the magnitude and extent of future climate change across Australian landscapes and by our ability to predict the associated ecological changes. Biodiversity managers will also need to consider the interactions with other processes that threaten the resilience of biodiversity, including how future societies themselves shape the landscape. Future natural resource management (NRM) plans will then need to allow for extensive changes in biodiversity that are not entirely predictable. Plans may need to focus on supporting biodiversity through these changes, including adjusting objectives to better cater for climate change. It is in this context that we present two parts of the story bringing biodiversity and climate change into NRM planning. Both Guides present new types of information about the potential for broad shifts in biodiversity in response to climate change applied to four terrestrial biological groups – vascular plants, mammals, reptiles and amphibians – for two plausible climate futures using the latest climate projection data. Our new measures of change in biodiversity: It is challenging to develop a synthesised understanding of biodiversity change from many individual species models. This first Guide therefore introduces the concept of ‘ecological similarity’ for assessing the potential for broad shifts in biodiversity, as a whole, in response to climate and land use change. It uses a form of community-level modelling that considers the implications of climate change on all species simultaneously within a single integrated process. We use ecological similarity as a basis to produce four specific measures that each provide a different view of the magnitude and nature of likely change in biodiversity. These new whole-of-biodiversity measures present a different perspective on how particular biological groups may respond to climate change and implications for how managers may plan to intervene. In this Guide, we suggest ways in which this new information can be used to support specific tasks in planning, and encourage planners to develop their own approaches to build on these practical suggestions. While the “intelligent” species of this planet continue the never ending talkfest on the merits or otherwise of responding to climate change the rest of the travellers on Planet Earth are speaking with their feet/roots/wings/ wriggly bits. The debate for them is irrelevant they need to move, and are, to ensure their own survival. We unfortunately, other than the main cause for the need for them to move, are often in the way. A dilemma for us all. You are a snail. You are a plant. You like where you are. The temperature’s right. It suits you. But then, gradually, over the years, it gets warmer. Not every day, of course, but on more and more days, the temperature climbs to uncomfortable highs, drying you out, making you tired, thirsty. Read on to find out what they do… An excellent presentation: Trees On The Move As Temperature Zones Shift 3.8 Feet (1.2m) A Day (19 February 2014) by Robert Krulwich 6 May 2014, National Geographic: How a Few Species Are Hacking Climate Change But in recent weeks, the general gloom has been pierced by two rays of hope: Reports have come in of unexpected adaptive ability in endangered butterflies in California and in corals in the Pacific. Two isolated reports don’t, of course, diminish the gravity of the global threat. But they do highlight how little we still know about nature’s ability to cope with climate change. “Most of the models that ecologists are putting out are assuming that there’s no adaptive capacity. And that’s silly,” says Ary Hoffmann, a geneticist at the University of Melbourne in Australia and the co-author of an influential review of climate change-related evolution. “Organisms are not static.” That species are on the move is becoming obvious not just to scientists but also to gardeners and nature-lovers everywhere. Butterflies are living higher up on mountains; trees are moving north in North America and Europe. In North Carolina, residents are still agog at encountering nine-banded armadillos, which have invaded the state from the south. A 2011 review of data on hundreds of moving species found a median shift to higher altitudes of 36 feet (11 meters) per decade and a median shift to higher latitudes of about 10.5 miles (17 kilometers) per decade. There’s also a clear warming-related trend in the timing of natural events. One study suggests that spring shifted 1.7 days earlier between 1954 and 2007. Insects are emerging earlier; birds are nesting earlier; plants are flowering and leafing out earlier. The latest of such natural events studies, out last month, shows that climate change has stretched out the wildflower bloom season in Colorado by 35 days. Read More here See Also: Larger Animals Show Greatest Response to Climate Change Climate change and invasive species Different species will respond to climate change in different ways. CSIRO researchers Mike Dunlop and Peter Brown outline three models of response The most prevalent model predicts that species will move gradually and at different rates as the climate changes – ‘gradual changes in distribution’ – to maintain a similar climatic niche. The obvious conservation response is to ensure that species are able to migrate, by removing barriers to movement and creating corridors to potential habitats. However, many species will not move: plants are often constrained by soils rather than climate and other species are constrained by biological factors such as competition or predation. Although the model is “intuitively appealing”, and allows for simple, directional predictions, Dunlop and Brown caution that the preference for it may not reflect reality. For invasive species, this model implies their ranges will also gradually change in response to changing climatic conditions. Another model – ‘rapid changes in distribution’ predicts range expansion for some species that can take advantage of changing conditions. Fire pioneers, for example, will benefit from more fires; wind- and water dispersed species may benefit from more cyclones and floods; and higher CO2 levels will give some plant species a competitive edge. This model is particularly pertinent for those invasive species likely to benefit from more extreme events or more CO2. The impact of these climate change “winners” may be detrimental to some native species. In some cases, native species that benefit from the changes may also become invasive. Conservation responses to this model include addressing the threats caused by climate change “winners”. A third model – ‘changes in abundance’ – predicts that climate change will affect the abundance of some species rather than their distribution. Some species will decline and others will proliferate, and that in turn will affect ecosystem structure and function. Species vulnerable to climate change may retract to climate refuges, such as cooler or wetter locations in their range. Some invasive species are likely to become more abundant and increase pressure on declining species. Conservation responses to this model include protection of refugia for declining species and control of threats deriving from more-abundant species. All three models are likely to account for some changes, and under each, it is likely that invasive species will strongly affect how native species and ecosystems fare under climate change. Read More here CSIRO: Weeds are one of the main threats to biodiversity and agriculture in Australia and under climate change will become an increasing management challenge for natural resource management (NRM) regions. The information presented on the adaptnrm website page shows how weeds and invasive plants are likely to respond to climate change as well as providing a framework for planning weed management under climate change. The Weeds and Climate Change Technical Guide is also available for download using this link. This site also features supporting materials and species-specific datasets through the CSIRO data access portal. ISC Fact Sheet: Invasive animals and climate change Invasive animals – particularly foxes, cats, rabbits and rats – have caused or contributed to dozens of extinctions in Australia, and threaten many of our most vulnerable native species. Goats, pigs, horses and other hard-hoofed feral animals cause serious degradation. As with native species, climate change will benefit some invasive animals and cause others to decline. However, because disturbance and stress to native species and ecological communities often benefit invasive species, and because climate change will bring new invasive threats, the overall threat from invasive species is likely to increase. In many cases the increased threats from invasive species are likely to exceed the direct threats of climate change to native species. Here are some examples of what can be expected: Range changes due to new temperature and rainfall patterns: New temperature and rainfall patterns may facilitate the establishment of new invaders and increase the impacts of others. There is already evidence of this occurring. After existing along the Victorian coast for almost a century, European green crabs (Carcinus maenas) invaded Tasmanian waters after a run of unusually warm winters in 1988 to 1991.4 As the climate warms, cane toads are predicted to expand southwards,5 and cats may be able to spread to some islands currently too wet for them that serve as sanctuaries from exotic predators.6 Tropical aquarium fish – the largest category of invasive animals in Australia – are likely to establish and spread further as waters become warmer. Invasion opportunities with extreme events: Climate change is predicted to increase the frequency or severity of extreme events, such as cyclones, floods, droughts and fires, to the benefit of some invasive animals. By linking outdoor ponds with waterways and waterways with each other, floods spread feral fish, such as cichlids (Cichlidae) and carp (Cyprinus carpio). Storms and cyclones can destroy fences, allowing animals to escape from deer farms, game reserves and zoos. During cyclone Larry more than 200 deer of various species escaped in the Wet Tropics. More fires could increase predation by cats and foxes on declining species, by removing protective vegetation cover. Predation after fires is believed to be reducing numbers of the endangered eastern bristlebird, and probably contributed to the disappearance of numbats from arid Australia. Increased vulnerability to feral threats: The stress imposed by climate change is likely to increase the susceptibility of species to invasive animals. Increased fox predation on pygmy possums in the Australian Alps is an example of this. The converse is also true – that species or ecosystems threatened by invasive species are likely to be more vulnerable to climate change. For example, the grazing pressure of rabbits, goats and other invasive herbivores reduces the resilience of native plants to drought. Human responses can increase threats: Some human responses to climate change may exacerbate feral animal problems. If water is spread between catchments to avert shortages, aquatic pests such as tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) will have an opportunity to spread. Farmers struggling with drought or floods are less likely to control feral animals – this may have led to an increase in the abundance of some pest species in NSW from 2002-04. Read More here Examples of “ecosystem” impacts & response 12 July, Climate News Network, Natural world feels the heat as temperatures soar: Birds, insects and trees are all under threat as the rise in gobal average temperatures makes drought and heatwaves much more likely. Extremes of heat − and an extra helping of drought − have begun to change the planet in small, subtle ways, and will almost certainly continue the process of change, according to new research. Bird species such as the Elegant Tern have begun to move north from the Gulf of California in Mexico, a species of ant that lives underground has shown it cannot take the heat, and the giant trees of the world’s forests may be at risk. The link between any single extreme of heat and drought, and global warming as a consequence of the emissions of greenhouse gases from human burning of fossil fuels, is almost impossible to prove, but climate science has begun to show that, in general, heatwaves and drought become more likely as global average temperatures soar. Atmospheric circulation: But the argument is not conclusive. Daniel Horton, research fellow in Earth system science at Stanford University, California, and colleagues show in the journal Nature that extremes of temperature in Europe and North America could be linked to changes in atmospheric circulation and to the distribution of heat and water vapour in the atmosphere. That still leaves open the question: is that because of some natural cycle, or a response to global warming? Kevin Trenberth, Distinguished Senior Scientist in the climate analysis section at the US National Centre for Atmospheric Research, and colleagues argue in Nature Climate Change that this is hardly an either/or question. Natural variability and human-induced climate change may both be at work in extreme events. So there could be other ways of putting the question. Given a flood, where did the moisture come from? Could it be linked to high ocean temperatures that in turn could be linked to human-induced climate change? Read More here 9 June 2015, University Santa Barbara, Predicting Tree Mortality: A National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis working group study analyzes a variety of factors contributing to forest die-offs. A combination of drought, heat and insects is responsible for the death of more than 12 million trees in California, according to a new study from UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS). Members of the NCEAS working group studying environmental factors contributing to tree mortality expect this number to increase with climate change. The study is the first of its kind to examine the wide spectrum of interactions between drought and insects….The western U.S. has been a hotspot for forest die-offs. Local economies in states like California and Colorado are highly dependent on the nature-based tourism and recreation provided by forests, which offer a scenic backdrop to the skiing, fishing and backpacking opportunities that draw so many people to live and play in the West. But lingering drought, rising temperatures and outbreaks of tree-killing pests such as bark beetles have spurred an increase in widespread tree mortality — especially within the past decade. Read More here 8 May 2015, Motherboard: North American Moose dying in droves as climate warming fuels disease, pests: North American moose are dying by the thousands as they struggle with soaring temperatures and health problems linked to disease and parasites that thrive in the heat, scientists are finding. In north east Minnesota alone, moose numbered about 8,000 a decade ago. Today, the population is down to 3,500. The story is similar throughout Canada, New Hampshire and Maine. “All across the southern edge of the range, from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Minnesota, Michigan, all across the southern fringe of their range, moose numbers are in a significant decline,” Eric Orff, biologist with the National Wildlife Federation, told PBS. Biologist Seth Moore has been taking samples of the Minnesota population since 2009. Of the 80 percent of collared moose that have died, 40 percent died from an infection known as brain worm, 20 percent died from a heavy winter tick load that sucks the blood from the animals, and the rest died from a combination of both, reports Motherboard. Both scourges are linked to warmer temperatures. Read More here 24 June 2015, Climate Network News, Global warming is accelerating loss of species: Human-induced climate change adds to threats vertebrates face from hunting and habitat loss as researchers warn that modern extinction rates are exceptionally high. Biologists have once again confirmed their own worst fears – that humans have launched a new phase of mass extinction. There have been five catastrophic episodes in the 500 million-year history of complex life, and humanity has now precipitated a sixth, according to a new study. Gerardo Ceballos, a researcher in the Department of Ecology Biodiversity at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and colleagues report in the journal Science Advances that their calculations are based on the most conservative possible estimates of extinction in recent human history. They compared those with the calculated “background”, or normal, rate of extinction throughout evolution, and came to the conclusion that vertebrate species are slipping away into the eternal night at least 114 times faster than they would if there were no humans around to hunt them, destroy their habitats or change the climates in which they had evolved. Read More here Key Information & Resource Sites Natural Ecosystems Network is one of four adaptation networks initiated by Australia’s National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF). It is hosted by James Cook University and Convened by Professor Stephen Williams at the Centre for Tropical Biodiversity and Climate Change. The Network brings together the people and knowledge from previous Freshwater, Marine and Terrestrial Biodiversity Adaptation Research Networks established during NCCARF Phase 1. The overall mission of the Network is to provide decision-makers with information to develop and implement strategies that will minimise the impacts of climate change on Australia’s Natural Ecosystems. ADAPTNRM: Climate change tools and resources for NRMs: Some of the challenges of adapting to climate change and some of the information needed to support adaptation cut across Australia’s regional boundaries. Regardless of which land uses, biomes, industries, and communities regional planners work with, there is a universal need for a planning approach that takes into account a variable and dynamic future. Many of the drivers of changes in weeds and biodiversity are national in scope but still highly relevant for regional planning. And the need to share insights and experiences across Australia and learn from each other has never been greater. Invasive Species Council is the main conservation group pressuring governments to do more about weeds, pests and diseases that threaten the nature of Australia.Changing climate – adaptation on the run or extinction

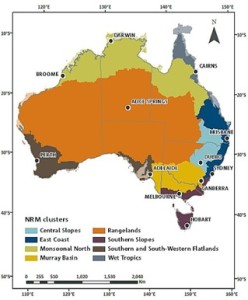

Impacts and adaptation information for Australia’s NRM regions

Animals can be surprisingly adaptable—but can they change quickly enough? As the Earth heats up, animals and plants are not necessarily helpless. They can move to cooler climes; they can stay put and adapt as individuals to their warmer environment, and they can even adapt as a species, by evolving. The big question is, will they be able to do any of that quickly enough? Most researchers believe that climate change is happening too fast for many species to keep up. (Related: “Rain Forest Plants Race to Outrun Global Warming.”)

15 July 2015, New York Times, After years of drought, wildfire rages in California: The Lake Fire started just before 4 p.m. on June 17. If rain and snow had arrived as scheduled in the winter, it might have been done in a day, at a cost of just a few acres. But with the drought turning soil to dust and trees to tinder, the fire, still smoking, has consumed a swath of national forest roughly the size of San Francisco. It has become the first big wildfire of a California season that threatens to become a terror. Between Jan. 1 and July 11, California fire officials have responded to more than 3,381 wildfires, 1,000 more than the average over the previous five years. The map below shows this year’s fires, as detected by satellite. There are blazes big and small all across the West, but wildfires have been especially concentrated along the mountain ranges of central California. Read More here

15 July 2015, New York Times, After years of drought, wildfire rages in California: The Lake Fire started just before 4 p.m. on June 17. If rain and snow had arrived as scheduled in the winter, it might have been done in a day, at a cost of just a few acres. But with the drought turning soil to dust and trees to tinder, the fire, still smoking, has consumed a swath of national forest roughly the size of San Francisco. It has become the first big wildfire of a California season that threatens to become a terror. Between Jan. 1 and July 11, California fire officials have responded to more than 3,381 wildfires, 1,000 more than the average over the previous five years. The map below shows this year’s fires, as detected by satellite. There are blazes big and small all across the West, but wildfires have been especially concentrated along the mountain ranges of central California. Read More here