What you will find on this page: trickle down does not work; world governance context; globalisation; national accounts; why isn’t it collapsing; what is missing in GDP (video); new economics; journey to downsizing; how we got ourselves into this mess; the story of stuff (video); degrowth to steady state economy; degrowth how to get there; key information & resource sites for changing the way we live – downsizing (video); LATEST NEWS; ; also refer to pages steady state economy; “cities responding“; “equity & social justice” as the issues are closely related

What is made up by man can be unmade: bigger is not better

The current way the world is run has had it’s day. It was made up by a small group of men in suits who created the “rules” for a specific purpose and now it is time to change them.

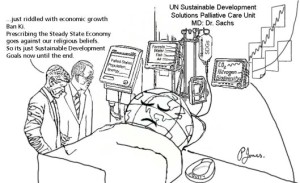

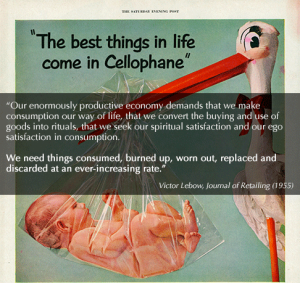

Latest News 25 April 2016, The Guardian, The Guardian view on the UN climate change treaty: now for some action. The danger of gala events like the official signing of the climate change treaty at the UN in New York on Friday, crowned with a guest appearance from Leonardo DiCaprio and with 60 heads of state in attendance, is the impression they create that the job is done. It was certainly a spectacular demonstration of global intent to get more than 170 signatures on the deal agreed in Paris in December at the first time of asking; but what matters is making it legally binding. For that, it must be not just signed but ratified by at least 55 countries, and it must cover 55% of emissions. Nor does the Paris deal go far enough. It was only a step on a long, hard road. The targets that each country set themselves do not go nearly far enough. Now the gap between reality and the ambition of holding global warming below 2C needs addressing. In Churchillian rhetoric, this is not the end, nor the beginning of the end, but it is the end of the beginning. Read More here 21 April 2016, ECOS/CSIRO, Systematically addressing disaster resilience in Australia could save billions. The cost of replacing essential infrastructure damaged by disasters will reach an estimated $17 billion in the next 35 years, according to the latest set of reports from the Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities.The reports, Building Resilient Infrastructure and the Economic Costs of Social Impact of Disasters, outline the costs associated with replacing essential infrastructure damaged by disasters and provide an overview of the direct costs of physical damage within the total economic cost of disasters. In 2015, the total economic costs of disasters exceeded $9 billion, a figure that is projected to double by 2030 and reach $33 billion per year by 2050 – funds that could be spent elsewhere on other major national projects. During the Roundtable’s launch of the reports at Parliament House last month, risk expert and CEO of reinsurer Munich Re, Heinrich Eder, noted that these projections are based only on economic and population growth. They do not even include the increasingly detectable effects of climate change. These are big, and socially traumatic, numbers. Long-term they have the same sort of potential to create holes in national and state budgets as our ageing population does—the subject of repeated Intergenerational Reports and eventual decisions about adjusting retirement age. Read More here 21 April 2016, The Conversation, Limits to growth: policies to steer the economy away from disaster. If the rich nations in the world keep growing their economies by 2% each year and by 2050 the poorest nations catch up, the global economy of more than 9 billion people will be around 15 times larger than it is now, in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). If the global economy then grows by 3% to the end of the century, it will be 60 times larger than now. The existing economy is already environmentally unsustainable. It is utterly implausible to think we can “decouple” economic growth from environmental impact so significantly, especially since recent decades of extraordinary technological advancement have only increased our impacts on the planet, not reduced them. Moreover, if you asked politicians whether they’d rather have 4% growth than 3%, they’d all say yes. This makes the growth trajectory outlined above all the more absurd. Others have shown why limitless growth is a recipe for disaster. I’ve argued that living in a degrowth economy would actually increase well-being, both socially and environmentally. But what would it take to get there? In a new paper published by the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, I look at government policies that could facilitate a planned transition beyond growth – and I reflect on the huge obstacles lying in the way. Measuring progress First, we need to know what we’re aiming for. It is now widely recognised that GDP – the monetary value of all goods and services produced in an economy – is a deeply flawed measure of progress.Read More here 18 April 2016, The Conversation, Australia’s carbon emissions and electricity demand are growing: here’s why. Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions are on the rise. Electricity emissions, which make up about a third of the total, rose 2.7% in the year to March 2016. Australia’s emissions reached their peak in 2008-2009. Since then total emissions have barely changed, but the proportion of emissions from electricity fell, largely due to falling demand and less electricity produced by coal. But over the last year demand grew by 2.5%, nearly all of this supplied by coal. In 2015 I wrote about concerns that Australia’s electricity demand and emissions would start increasing again. This has now come true. So what’s driving the trend? Why did demand fall? To understand this trend we need to look at data from Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM), which accounts for just under 90% of total Australian electricity generation. While the NEM doesn’t include Western Australia or the Northern Territory, it has much better publicly available data. The chart below shows electricity generation from June 2009 to March 2016. End latest news It is now official – IMF Report: trickle down does NOT work.(About time they caught up with reality!) June 2015, International Monetary Fund Report: Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality: A Global Perspective: We should measure the health of our society not at its apex, but at its base.” Andrew Jackson Widening income inequality is the defining challenge of our time. In advanced economies, the gap between the rich and poor is at its highest level in decades. Inequality trends have been more mixed in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs), with some countries experiencing declining inequality, but pervasive inequities in access to education, health care, and finance remain. Not surprisingly then, the extent of inequality, its drivers, and what to do about it have become some of the most hotly debated issues by policymakers and researchers alike. Against this background, the objective of this paper is two-fold. First, we show why policymakers need to focus on the poor and the middle class. Earlier IMF work has shown that income inequality matters for growth and its sustainability. Our analysis suggests that the income distribution itself matters for growth as well. Specifically, if the income share of the top 20 percent (the rich) increases, then GDP growth actually declines over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down. In contrast, an increase in the income share of the bottom 20 percent (the poor) is associated with higher GDP growth. The poor and the middle class matter the most for growth via a number of interrelated economic, social, and political channels. Read full report here Before people can change things there needs to be an understanding of what is currently in place and why it isn’t working. The most glaring failures of the economic systems imposed on the world is that they fundamentally rely on the unsustainable assertion of never ending growth and the belief that money in/money out is the only way to measure progress. You do not need to be an economist, maybe it is better not to be one, to see that this won’t work on a finite planet. Governance of the global economy – briefly The governance functions of today’s global economy are divided between the Bretton Woods Agreement (now, possibly the “Washington Consensus” or some other manifestation) and the United Nations System of National Accounts which is the basis for a country’s GDP calculations. Bretton Woods Agreement: In July 1944 (only 71 years ago) the modern economic system came into being in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, USA, where delegates from forty-four allied countries gathered to devise institutions meant to foster multilateral cooperation, financial stability and post-war economic reconstruction. The “ideas” (not laws cut in stone) discussed at this meeting came primarily from two men – John Keynes (Britain) and Harry White (USA). A central element of what Keynes and White were trying to create was a way to have stable exchange rates and prices and economic growth. The plan involved nations agreeing to a system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates where the currencies were pegged against the dollar, with the dollar itself convertible into gold. So in effect this was a: gold – dollar exchange standard. Two international institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were created. A key part of their function was to replace private finance as a more reliable source of lending for investment projects in developing states. At one stage John Keynes proposed an International Clearing Union (ICU) as a way to regulate the balance of trade. His concern was that countries with a trade deficit would be unable to climb out of it, paying ever more interest to service their ever greater debt, and therefore stifling global growth. However, Harry White, representing America which was the world’s biggest creditor said “We have been perfectly adamant on that point. We have taken the position of absolutely no.” Instead he proposed an International Stabilisation Fund (now the IMF), which would place the burden of maintaining the balance of trade on the deficit nations, and imposing no limit on the surplus that rich countries could accumulate. Basically the Agreement meant: open markets; lowering of trade barriers; movement of capital and the end of economic nationalism. Then what happened? The rules changed: In 1971 the central role of the dollar became a problem as international demand eventually forced the US to run a persistent trade deficit, which undermined confidence in the dollar. This, together with the emergence of a parallel market for gold where the price soared above the official US mandated price, led to speculators running down the US gold reserves. Even when convertibility was restricted to nations only, some, notably France, continued building up hoards of gold at the expense of the US. Eventually these pressures caused President Nixon to end all convertibility into gold on 15 August 1971. Unusually, this decision was made without consulting members of the international monetary system or even his own State Department, and was soon dubbed the “Nixon Shock”. Goodness one man changed the rules! With the US picking up its bat and ball (removing its currency from the gold standard) Bretton Woods Agreement was no longer workable. This event marked the effective end of the Bretton Woods systems; attempts were made to find other mechanisms to preserve the fixed exchange rates over the next few years, but they were not successful, resulting in a system of floating exchange rates. They have been fiddling around the edges ever since; hence the “Washington Consensus”; “New Bretton Woods”… It’s broke… please refer to the tribal wisdom of the Dakota Indians. However the Bretton Woods institutions remained: IMF, World Bank and then in 1995 the World Trade Organisation joined them. The founders of the United Nations intended that responsibility for managing global economic affairs–including the overall supervision and policy direction of the Bretton Woods institutions–would fall under the jurisdiction of the United Nations General Assembly and its Economic and Social Council. At least since 1981, however, the U.S. government has actively undermined the UN’s ability to fulfill this mandate. It has instead supported the Bretton Woods institutions in acting as global governments unto themselves, imposing their will on nation states in disregard of both the democratic will of their own people and the terms of UN conventions and treaties. We are now dealing with the phenomena of globalisation and an ever increasing number of international trade agreements enveloping more and more countries where massive multinational corporations call the shots rather than national governments. And what has this to do with climate change? Everything! Globalisation seems to be looked on as an unmitigated “good” by economists. Unfortunately, economists seem to be guided by their badly flawed models; they miss real-world problems. In particular, they miss the point that the world is finite. We don’t have infinite resources, or unlimited ability to handle excess pollution. So we are setting up a “solution” that is at best temporary. Economists also tend to look at results too narrowly–from the point of view of a business that can expand, or a worker who has plenty of money, even though these users are not typical. In real life, the business are facing increased competition, and the worker may be laid off because of greater competition. For a list of reasons why globalization is not living up to what was promised, and is, in fact, a very major problem go here Our Finite World The other side of the coin: National Accounts – GDP United Nations System of National Accounts – the basis for countries producing their Gross Domestic Product (GDP): Definition: GDP measures the total value of final goods and services produced within a given country’s borders. It is the most popular method of measuring an economy’s output and is therefore considered a measure of the size of an economy. Unfortunately the interpretation of the GDP has gone far beyond its basic economic measurement to somehow stand for how “well” a nation is developing/progressing and therefore compounds this mistake by using it to make broad policy decisions that can have drastic consequences for the well being of its people and the environment. It’s very “simplicity” fails to capture many things. The following are the basics of what is not captured in GDP: Most glaringly, GDP does not capture the distribution of growth and, as a result, cannot reflect inequality. GDP cannot distinguish between a positive economic indicator, like increased spending due to more disposable income, and a negative economic indicator, like increased spending on credit cards due to loss of wages or declining real value of wages. GDP also does not capture the value added by volunteer work, and does not capture the value of caring for one’s own children. For example, if a family hires someone for childcare, that counts in GDP accounting. If a parent stays home to care for their child, however, the value is not counted in GDP. In addition, the enormous value of the country’s natural capital and ecosystems is also not reflected in GDP. Preserving the country’s natural resources—essential to our current and future wealth—is not counted, but exploiting them in an unsustainable manner is. Only when natural resources are sold or somehow commoditized do they show up in GDP calculations. For example, if all of the fish in the sea were caught and sold in in one year, global GDP would skyrocket, even though the fishing industry itself would collapse and the broader ecosystem would be damaged irrevocably. Our economic growth is increasing at a rate that cannot be ecologically sustained. The problem with over reliance on GDP is the role that it plays in formulating policy and setting priorities. If policymakers considered GDP only as a measure of raw market economic activity in conjunction with many other metrics, the flaws in it would be less important. If poverty rates, inequality levels, natural capital accounts, and other metrics were taken into account as heavily as GDP, then different policies and priorities would begin to emerge. Instead, we are now focused solely on increasing GDP, even though increasing poverty rates, inequality levels, and other societal indicators show that in many ways, we are experiencing growth without progress. For example, if policymakers relied on measures of natural capital as well as GDP, the value of preserving forests as “carbon sinks” and air purifiers would provide economic justification for adopting policies to preserve natural resources. Likewise, if economists and officials considered decreasing inequality as central to economic progress, more progressive taxation and pro-worker trade policies would be more attractive. Source: Demos Other sources: Wikipedia; Living Economies Forum; Marilyn Waring, “Counting For Nothing”. Refer also to: Counting for something! Recognising women’s contribution to the global economy through alternative accounting systems by Marilyn Waring; Women Reinventing Globalism. If things are so bad why don’t we see complete collapse of the system? GDP: We are measuring the wrong things 7 May 2013, Marilyn Waring, Making visible the invisible: commodification is not the answer: If you are invisible as a producer in the GDP, you are invisible in the distribution of benefits in the economic framework of the national budget. As feminists we must embrace an ecological model if we are to transform economic power, and the market and commodification must be seen as the servants of such an approach. The system of national accounts and this framework, which brought us Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the system imposed on all nation states arising from Sir Richard’s Stones work entitled : The British National Income and how to pay for the war – still effectively measures ‘how best to pay for the war’ – demonstrated most markedly in countries where the GDP goes down after a peace settlement holds….. Implications for transformation As long as water holds out, the implications for the international imposition, of national environmental accounts as market valuations, can’t happen. But economics only values the deletion, depletion, deterioration and extraction of natural resources. The strategic imperative we are interested in is not to find a market value for characteristics of the environment, but to collect the baseline data about these characteristics – the quality of air, the remaining boreal forests, the impacts of climate change. Translating these characteristics to market prices is a stupid idea for many reasons, but a key is that when the environment is abstracted to a market value, it loses all the characteristics that make it possible to make strategic policy decisions. Read More here Genuine progress indicator, or GPI, is a metric that has been suggested to replace, or supplement, gross domestic product (GDP) as a measure of economic growth. GPI is designed to take fuller account of the health of a nation’s economy by incorporating environmental and social factors which are not measured by GDP. For instance, some models of GPI decrease in value when the poverty rate increases.[1] The GPI is used in green economics, sustainability and more inclusive types of economics by factoring in environmental and carbon footprints that businesses produce or eliminate. “Among the indicators factored into GPI are resource depletion, pollution, and long-term environmental damage. Read More here GPI system of sustainable wellbeing accounts: …..For more than 50 years economists have been measuring the economic well-being of nations using a System of National Accounts (SNA) and a broad measure called the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, the SNA and GDP measure well-being through a most myopic lens; the more money changing hands for goods and services produced and sold in the market the more it is assumed our economic wellbeing rises. This very narrow measurement system is fundamentally flawed. First, it does accord with the letter and meaning of the words “economic” and “wealth.” Second, it fails to measure the physical realities or conditions that common sense would argue contributes to our genuine well-being – our physical, mental, spiritual health, the social cohesion of our households and communities, and the integrity of the natural environment. Read More here An example: Alberta’s Genuine Progress Indicator Published on 14 Aug 2013:A brief overview of the National Sustainability Council’s report ‘Sustainable Australia 2013’ by Council Chair John Thwaites at a launch event in Melbourne for the latest Sustainable Campus Group report. Read More here 9 June 2015, Steady State NSW: To close for comfort?? When CASSE NSW member Phil Jones posted the cartoon below onto the Sustainable Development Goals Facebook page it was taken down. I present the following as a selection of new ways people are looking at how our “economy” (whatever size it might be) can be adapted to the changing planetary conditions we are experiencing and will experience into the future. If you are interested in this field, they are for your consideration and further exploration. Also refer to the “Steady State Economy” page for greater detail and more links to other websites on this topic 23 June 2015, Post Carbon Institute, Economics vs Economy: Economic theories, though social constructions, can reflect reality to varying degrees. In the face of dire environmental challenges, adopting a realistic theory is key to the survival of global civilization. The neoliberal emphasis on limitless growth and monetary flows, a relic of nineteenth century thinking, abstracts away from biological conditions. By contrast, ecological economics—as distinct from environmental economics, which remains wedded to the neoliberal growth paradigm—understands the economy as a subsystem of the ecosphere and envisions a steady-state economy embedded within natural constraints. Achieving this equitably will require significant redistribution of wealth and income, reduction of material throughput, and a transition away from fossil fuels. Although the neoliberal paradigm remains dominant, its lack of fitness to current realities gives hope that an ecological alternative could ascend. To begin, it is important to distinguish between “the economy” and “economics.” Both are made-up concepts, but with a significant difference. We define the economy as that set of activities by which human agents identify, develop/exploit, process, and trade in scarce resources. It generally encompasses everything associated with the production, allocation, exchange, and consumption of valuable goods and services, including the behavior of various agents engaged in economic activity. Different economies vary considerably in sophistication and organizational structure. However, all economies are real phenomena; people in every human society from primitive tribes through modern nation-states engage in economic activities as defined. “Economics,” by contrast, is pure abstraction. It is that academic discipline dedicated to dissecting, analyzing, modeling, and otherwise describing the economy in simplified terms. Academic economists engage in the social construction of formalized models—verbal and arithmetic “paradigms”—about how the real economy works. Read More here The Ellen MacArthur Foundation believes that the circular economy provides a coherent framework for systems level re-design and as such offers us an opportunity to harness innovation and creativity to enable a positive, restorative economy. Here you will find a series of articles to help familiarise yourself with the circular economy model, its principles, related schools of thought, and an overview of circular economy news from around the world. Circular Economy Principles: New Economics Foundation (NEF) is the UK’s leading think tank promoting social, economic and environmental justice. Our aim is to transform the economy so that it works for people and the planet. The UK and most of the world’s economies are increasingly unsustainable, unfair and unstable. It is not even making us any happier – many of the richest countries in the world do not have the highest wellbeing. From climate change to the financial crisis it is clear the current economic system is not fit for purpose. We need a Great Transition to a new economics that can deliver for people and the planet. NEF’s mission is to kick-start the move to a new economy through big ideas and fresh thinking. We do this through: The New Economy Coalition (NEC) is a network of organizations imagining and building a future where people, communities, and ecosystems thrive. Together, they are creating deep change in our economy and politics—placing power in the hands of people and uprooting legacies of harm—so that a fundamentally new system can take root. The Schumacher Centre for a New Economics aims to educate the public about an economics that supports both people and the planet. They believe that a fair and sustainable economy is possible and that citizens working for the common interest can build systems to achieve it. They recognize that the environmental and equity crises we now face have their roots in the current economic system. The Green Economy Coalition (GEC) is a diverse set of organisations and sectors from NGOs, research institutes, UN organisations, business to trade unions. They have come together because they recognise that our economy is failing to deliver either environmental sustainability or social equity. In short, our economic system is failing people and the planet. Their vision is one of a resilient economy that provides a better quality of life for all within the ecological limits of the planet. Their mission is to accelerate the transition to a new green economy. “Consumerism is a gross failure of imagination, a debilitating addiction that degrades nature and doesn’t even satisfy the universal human craving for meaning.” How did we manage to get ourselves into this mind set? 14 April 2015. Richard Heinberg from Post Carbon Institute explains…..You and I consume; we are consumers. The global economy is set up to enable us to do what we innately want to do—buy, use, discard, and buy some more. If we do our job well, the economy thrives; if for some reason we fail at our task, the economy falters. The model of economic existence just described is reinforced in the business pages of every newspaper, and in the daily reportage of nearly every broadcast and web-based financial news service, and it has a familiar name: consumerism. Consumerism also has a history, but not a long one. True, humans—like all other animals—are consumers in the most basic sense, in that we must eat to live. Further, we have been making weapons, ornaments, clothing, utensils, toys, and musical instruments for thousands of years, and commerce has likewise been with us for untold millennia. What’s new is the project of organizing an entire society around the necessity for ever-increasing rates of personal consumption….. Read More here The Story of Stuff, originally released in December 2007, is a 20-minute, fast-paced, fact-filled look at the underside of our production and consumption patterns. The Story of Stuff exposes the connections between a huge number of environmental and social issues, and calls us together to create a more sustainable and just world. It’ll teach you something, it’ll make you laugh, and it just may change the way you look at all the Stuff in your life forever. Read More here. Access more “Stories of….” here 14 September 2015, Worldwatch Institute, Five Eye-opening Global Trends You Should Know It’s not easy to keep track of the complex ways in which our everyday choices have an impact on a global scale. But as the world’s population surpasses 7 billion, each of our actions—positive or negative—gets multiplied. Read on to learn about five global trends from our latest publication, Vital Signs: The Trends That Are Shaping Our Future, that show that our consumption choices affect more than ourselves—they affect the environment and the lives and livelihoods of millions. Read More here for: Who’s driving the trend? What does this trend mean? What can be done? Source: Worldwatch Institute Infograph Degrowth to a steady state economy 26 June 2015, The Conversation, If everyone lived in an ‘ecovillage’, the Earth would still be in trouble: We are used to hearing that if everyone lived in the same way as North Americans or Australians, we would need four or five planet Earths to sustain us. This sort of analysis is known as the “ecological footprint” and shows that even the so-called “green” western European nations, with their more progressive approaches to renewable energy, energy efficiency and public transport, would require more than three planets. How can we live within the means of our planet? When we delve seriously into this question it becomes clear that almost all environmental literature grossly underestimates what is needed for our civilisation to become sustainable. Only the brave should read on…. Read More here – if you are brave! 2 October 2014, The conversation, Life in a ‘degrowth’ economy, and why you might actually enjoy it: What does genuine economic progress look like? The orthodox answer is that a bigger economy is always better, but this idea is increasingly strained by the knowledge that, on a finite planet, the economy can’t grow for ever. This week’s Addicted to Growth conference in Sydney is exploring how to move beyond growth economics and towards a “steady-state” economy. But what is a steady-state economy? Why it is it desirable or necessary? And what would it be like to live in? We used to live on a planet that was relatively empty of humans; today it is full to overflowing, with more people consuming more resources. We would need one and a half Earths to sustain the existing economy into the future. Every year this ecological overshoot continues, the foundations of our existence, and that of other species, are undermined. At the same time, there are great multitudes around the world who are, by any humane standard, under-consuming, and the humanitarian challenge of eliminating global poverty is likely to increase the burden on ecosystems still further. Meanwhile the population is set to hit 11 billion this century. Despite this, the richest nations still seek to grow their economies without apparent limit. Like a snake eating its own tail, our growth-orientated civilisation suffers from the delusion that there are no environmental limits to growth. But rethinking growth in an age of limits cannot be avoided. The only question is whether it will be by design or disaster. The idea of the steady-state economy presents us with an alternative. This term is somewhat misleading, however, because it suggests that we simply need to maintain the size of the existing economy and stop seeking further growth. But given the extent of ecological overshoot – and bearing in mind that the poorest nations still need some room to develop their economies and allow the poorest billions to attain a dignified level of existence – the transition will require the richest nations to downscale radically their resource and energy demands. This realisation has given rise to calls for economic “degrowth”. To be distinguished from recession, degrowth means a phase of planned and equitable economic contraction in the richest nations, eventually reaching a steady state that operates within Earth’s biophysical limits. Read More here Simplicity Institute Publications Access pdf: Retrofitting the Suburbs for the Energy Descent Future Access pdf: Degrowth and the Carbon Budget: Powerdown Strategies for Climate Stability Access pdf: The Deep Green Alternative:Debating Strategies of Transition Access pdf: Degrowth Implies Voluntary Simplicity: Overcoming Barriers to Sustainable Consumption Key information & resource sites for changing the way we live – downsizing “In Transition 2.0” above, is the latest full length film about the Transition movement. It’s an amazing story about how Transition groups around the world are responding to the challenges of depleting and costly energy resources, financial instability and environmental change. To access the film go here Transition Towns Australia: Transition Towns are towns all over the globe, who are actively planning and striving to become sustainable and resilient, to be better prepared for the challenges ahead. You will find a list of Transition Towns located within Australia here. Community Information Resource Center, CIRC is a networking hub and information source dedicated to building a better world. They work at all levels from local to global, sharing important information, connecting people, and catalysing the development of healthy self-reliant communities. The key areas covered are: Money, banking and finance; Land tenure, property ownership, and environment; Taxation and public revenue; Government, law, and public policy; Corporations and the centralization of power; Technology choices Growthbusters Hooked on Growth is a 54-minute, non-profit documentary being shown around the world by organizations, community groups and individuals interested in moving the world toward sustainability. A documentary exploring the forces that fuel our worship of growth everlasting. Their website has many links relating to downsizing: consumption growth; economic growth; population growth: urban growth Post Growth Institute is an international group exploring and inspiring paths to global prosperity that don’t rely on economic growth. Their mission is to build and empower a broad-based global movement for identifying, inspiring and implementing new approaches to global well-being. Post growth in action Resilience.org is both an information clearinghouse and a network of action-oriented groups. Its focus is on building community resilience in a world of multiple emerging challenges: the decline of cheap energy, the depletion of critical resources like water, complex environmental crises like climate change and biodiversity loss, and the social and economic issues which are linked to these: resources; groups & examples; community guide Thriving Resilient Communities Collaboratory (TRCC) connects the growing community resilience movement to more of itself in support of large-scale social transformation towards a just and thriving society. We are an action learning community of practice that hosts deep dialogues and gatherings, seeds and incubates collaborative projects, and fosters synergy among North American leaders including Art of Hosting, BayLocalize, Bioneers, Evolver, Movement Generation, Post Carbon Institute, Shareable, TransitionUS, and more. tools & approaches includes more links The NCN Alternative Money System team was created to collect information on what schemes already exist, to discuss the prospects of doing away with money systems and using a resource-based system instead, and ways of financing new civilization projects, implementing experimental schemes, and more. Reinventing Money: The mission of this site is to demystify money and liberate the process of exchange by making available important documents and resources from the past and present which can contribute to the advancement of economic democracy, self-determination, and global harmony. Visit the Beyond Money site for more complete coverage of the work of Thomas H. Greco, Jr’s work and developments of interest to practitioners and students. Transition Network is a charitable organisation whose role is to inspire, encourage, connect, support and train communities as they self-organise around the Transition model, creating initiatives that rebuild resilience and reduce CO2 emissions Per Square Mile: If the world’s population lived like…an infographic that shows how big a city would have to be to house the world’s 7 billion people. Also it compares different countries and how many resources their people—and their lifestyles—use. For countries, the differences are far, far greater than for cities. The Simplicity Institute is an education and research centre seeking to: seed a revolution in consciousness that highlights the urgent need to move beyond growth-orientated, consumerist forms of life; envision and defend a ‘simpler way’ of life at a time when the old myths of progress, techno-optimism, and affluence are failing us; transform the overlapping crises of civilisation into opportunities for ‘prosperous descent’. Publications; Take Action. Sharing the World’s Resources: STWR is an independent civil society organisation campaigning for a fairer sharing of wealth, power and resources within and between nations.Through our research and activities, we make a case for integrating the principle of sharing into world affairs as a pragmatic solution to a broad range of interconnected crises that governments are currently failing to address – including hunger, poverty, climate change, environmental degradation, and conflict over the world’s natural resources. For an overview of STWR’s perspective on strengthening and scaling up all genuine forms of economic sharing, read STWR’s Primer on global economic sharing or visit our introductory web pages. The Centre for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE): Perpetual economic growth is neither possible nor desirable. Growth, especially in wealthy nations, is already causing more problems than it solves. Recession isn’t sustainable or healthy either. The positive, sustainable alternative is a steady state economy. Investigating alternatives. Steady State NSW is run by the NSW Chapter of The Centre for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE). It contains news about the NSW Chapter (including details of meetings) plus interesting publications, organisations and events that NSW members come across.Reading List (excellent resource) EcoVillages – Lessons for sustainable communities: examples; learning resources  Richard Heinberg explains in his article “Fingers in the Dike”: The 19th century novel Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates by American author Mary Mapes Dodge features a brief story-within-the-story that has become better known in popular culture than the book itself. It’s the tale of a Dutch boy (in the novel he’s called simply “The Hero of Haarlem”) who saves his community by jamming his finger into a leaking levee. The boy stays all night, despite the cold, until village adults find him and repair the leak. His courageous action in holding back potential floodwaters has become celebrated in children’s literature and art, to the point where it serves as a convenient metaphor. Here in early 21st century there are three dams about to break, and in each case a calamity is being postponed—though not, in these cases, by the heroic digits of fictitious Dutch children. A grasp of the status of these three delayed disasters, and what’s putting them off, can be helpful in navigating waters that now rise slowly, though soon perhaps in torrents. Read More here

Richard Heinberg explains in his article “Fingers in the Dike”: The 19th century novel Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates by American author Mary Mapes Dodge features a brief story-within-the-story that has become better known in popular culture than the book itself. It’s the tale of a Dutch boy (in the novel he’s called simply “The Hero of Haarlem”) who saves his community by jamming his finger into a leaking levee. The boy stays all night, despite the cold, until village adults find him and repair the leak. His courageous action in holding back potential floodwaters has become celebrated in children’s literature and art, to the point where it serves as a convenient metaphor. Here in early 21st century there are three dams about to break, and in each case a calamity is being postponed—though not, in these cases, by the heroic digits of fictitious Dutch children. A grasp of the status of these three delayed disasters, and what’s putting them off, can be helpful in navigating waters that now rise slowly, though soon perhaps in torrents. Read More here

The journey to downsizing