What you will find on this page: How Australia is cooking the emissions books; Australia: Per capita: how much CO2 does the average person emit? (interactive); your greenwashing guide; Aust drops plans to use Kyoto credits; Oz govt dodgy accounting; Aust rising emissions; Australia needs to stop pretending we’re tackling climate change; numbers are out; new energy target – drop the “clean & ignore climate; States leading the way (report) release of Oz emissions 2016; unpacking Finkel report; Oz emissions rise; Fed budget climate policy silence; State renewables bashing continues; Australian climate politics in 2017: a guide for the perplexed; what did Malcolm have to say in 2012? latest example where political interest out weigh commonsense and foresight; carbon budget blowout or the continuance of creative accounting; beyond the limits report & Paris temperature check; global energy efficiency report; Great Barrier Reef saga; National Greenhouse & Energy information; emissions reality check; Paris policy brief; Australia’s global pledge; KYOTO commitment; Safeguard Mechanism; Emissions Reduction Fund; first auction results; second auction results; Direct Action; Renewable Energy Target. Also refer to “Global Action/Inaction” and “Fairyland of 2 degrees” pages as issues are related

Where does Australia stand? When it’s way of life depends on fossil fuel exports

Latest News 2 July 2018, Carbon Brief, Analysis: ‘Global’ warming varies greatly depending where you live. As part of the Paris Agreement on climate change, the international community committed in 2015 to limit rising global temperatures to “well below” 2C by the end of the 21st century and to “pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5C”. However, these global temperature targets mask a lot of regional variation that occurs as the Earth warms. For example, land warms faster than oceans, high-latitude areas faster than the tropics, and inland areas faster than coastal regions. Furthermore, global human population is concentrated in specific regions of the planet. Here, Carbon Brief analyses how much warming people will actually experience where they live, both today and under future warming scenarios. The warming experienced by people is typically higher than the global average warming. In a world where warming is limited to “well below” 2C about 14% of the population will still experience warming exceeding 2C. In the worst-case scenario of continued growth in emissions, about 44% of the population experiences warming over 5C – and 7% over 6C – in 2100. Warming is not globally uniform Different parts of the world respond in different ways to warming from increasing greenhouse gas concentrations. For example, ocean temperatures increase more slowly than land temperatures because the oceans lose more heat by evaporation and they have a larger heat capacity. High-latitude regions – far north or south of the equator – warm faster than the global average due to positive feedbacks from the retreat of ice and snow. An increased transfer of heat from the tropics to the poles in a warmer world also enhances warming. This phenomenon of more rapidly warming high latitudes is known as polar amplification. Read more here

30 June 2018, The Guardian, ‘We’ve turned a corner’: farmers shift on climate change and want a say on energy. Out in the bush, far from the ritualised political jousting in Canberra, attitudes are changing. Regional Australia has turned the corner when it comes to acknowledging the reality of climate change, says the woman now charged with safeguarding the interests of farmers in Canberra. Fiona Simson, a mixed farmer and grazier from the Liverpool plains in northern New South Wales, and the president of the National Farmers’ Federation, says people on the land can’t and won’t ignore what is right before their eyes. “We have been experiencing some wild climate variability,” Simson tells Guardian Australia’s politics podcast. “It’s in people’s face”. “While we are a land of droughts and flooding rains, absolutely at the moment people are seeing enormous swings in what would be considered usually normal. They are getting all their rainfall at once, even though they end up with an annual rainfall that’s the same, it’s all at once, or it’s in so many tiny insignificant falls that it doesn’t make any difference to them. And the heat. We’ve had some record hot summers and some weird swings in seasons”. Simson acknowledges there are “always going to be some outliers who are going to have some wild ideas” in farming or in any other sector of the Australian economy but she says “overwhelmingly, I think it’s got to the point where the science is very acceptable”. Read more here 27 June 2018, Climate Homes News, Leaked final government draft of UN 1.5C climate report – annotated. A draft summary of the most important climate science report of 2018, published here annotated with changes from the previous version. What is this document? This is the second draft of the summary for policymakers of the special report on 1.5C. It has been compiled by climate scientists from around the world. A draft, which was published by Climate Home News in February, was circulated to the scientific community for review earlier this year. The latest version, dated 4 June, has been sent to governments for comments on the ‘summary for policymakers’ (see below). The review runs until 29 July. What is a ‘summary for policymakers’? The full report, known as the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5C, will run to hundreds of pages of scientific data and findings. This is shortened set of conclusions and findings drawn from the larger report designed to provide information in a useable way for decision makers. Throughout the text you’ll see references to chapters in the larger report in curved brackets: eg. {2.3,2.5.3}. Read More here 26 June, Carbon Brief, Guest post: Unprecedented summer heat in Europe ‘every other year’ under 1.5C of warming. As summer gets underway in the northern hemisphere, much of Europe has already been basking in temperatures of 30C and beyond. But while the summer sun sends many flocking to the beach, with it comes the threat of heatwaves and their potentially deadly impacts. Tens of thousands of people across Europe died in heatwaves in 2003 and 2010, for example, while the “Lucifer” heatwave last year fanned forest fires and nearly halved agricultural output in some countries. With international ambition to limit global temperature rise to “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels now enshrined in the Paris Agreement, we have examined what impact that warming could have on European summer temperatures. Our results, published today in Nature Climate Change, find that more than 100 million Europeans will typically see summer heat that exceeds anything in the 1950-2017 observed record every other year under 1.5C of warming – or in two of every three years under 2C. Human influence on European climate There has been a substantial amount of work showing that recent heatwaves and hot summers in Europe have been strongly influenced by human-caused climate change. This includes the very first “event attribution” study that made a direct connection between human-caused climate change and Europe’s record hot summer of 2003. As a densely populated continent, recent hot summers and heatwaves have hit Europe withspikes in mortality rates. Europe is also a particularly good location to study the implications of the Paris Agreement limits because it has among the longest and highest quality climate data in the world. This means we have a better understanding of what past summers in Europe have been like and we can evaluate our climate model simulations with a higher degree of confidence, relative to other regions of the world. In our study, we looked at the hottest average summer temperatures across Europe since 1950 and found that for most of the continent these occurred in 2003, 2006 or 2010. There are exceptions, of course. For example, in Central England the hottest summer remains 1976. You can see this in the graphic below, which maps the decade of the hottest summer across Europe. The darker the shading, the more recently the record occurred. Read more here End Latest News

How Australia is cooking the emissions books

To understand how it has happened you need to follow the changing rules of global emission tracking:

23 May 2024, The Conversation: What is ‘Net Zero’, anyway? A short history of a monumental concept. Last month, the leaders of the G7 declared their commitment to achieving net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest. Closer to home, the Albanese government recently introduced legislation to establish a Net Zero Economy Authority, promising it will catalyse investment in clean energy technologies in the push to reach net zero. Pledges to achieve net zero emissions over the coming decades have proliferated since the United Nation’s 2021 Glasgow climate summit, as governments declare their commitments to meeting the Paris Agreement goal of holding global warming under 1.5°C. But what exactly is “net zero”, and where did this concept come from? Stabilising greenhouse gases In the early 1990s, scientists and governments were negotiating the key article of the UN’s 1992 climate change framework: “the stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic [human-caused] interference with the climate system”. How to achieve that stabilisation – let alone define “dangerous” climate change – has occupied climate scientists and negotiators ever since. From the outset, scientists and governments recognised reducing greenhouse gas emissions was only one side of the equation. Finding ways to compensate or offset emissions would also be necessary. The subsequent negotiation of the Kyoto Protocol backed the role of forests in the global carbon cycle as carbon sinks. Read more here

June 2022, Breakthrough Commentary: Model-based net-zero scenarios, including those of the IPCC, aren’t worth the paper they are written on, say leading economists. World-leading economists have blown a hole right through the middle of the main tool used to produce the net-zero scenarios embraced by climate policymakers. In a new paper, Sir Nicholas Stern, Nobel Laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz and Charlotte Taylor conclude that climate-energy-economy Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), which are the key tool in producing net-zero scenarios, “have very limited value in answering the two critical questions” of the speed and nature of emissions reductions and “fail to provide much in the way of useful guidance, either for the intensity of action, or for the policies that deliver the desired outcomes”. The research paper is The economics of immense risk, urgent action and radical change: towards new approaches to the economics of climate change. Now this is a big thing, because IAMs are at the centre of the IPCC Working Group III report on mitigation, and “have played a major role in IPCC reports on policy, which, in turn, have played a prominent role in public discussion. They continue to play a very powerful role in the research activities of economists working on climate change.” And it is not just the IPCC. The net-zero plans which are the focus of international discussion — such as those of the International Energy Agency and the world’s bankers (Network for Greening the Financial System) — are completely dependent on IAMs. Read more here

20 August 2024, The Conversation: The overshoot myth: you can’t keep burning fossil fuels and expect scientists of the future to get us back to 1.5°C. Record breaking fossil fuel production, all time high greenhouse gas emissions and extreme temperatures. Like the proverbial frog in the heating pan of water, we refuse to respond to the climate and ecological crisis with any sense of urgency. Under such circumstances, claims from some that global warming can still be limited to no more than 1.5°C take on a surreal quality. For example, at the start of 2023’s international climate negotiations in Dubai, conference president, Sultan Al Jaber, boldly stated that 1.5°C was his goal and that his presidency would be guided by a “deep sense of urgency” to limit global temperatures to 1.5°C. He made such lofty promises while planning a massive increase in oil and gas production as CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. We should not be surprised to see such behaviour from the head of a fossil fuel company. But Al Jaber is not an outlier. Scratch at the surface of almost any net zero pledge or policy that claims to be aligned with the 1.5°C goal of the landmark 2015 Paris agreement and you will reveal the same sort of reasoning: we can avoid dangerous climate change without actually doing what this demands – which is to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry, transport, energy (70% of total) and food systems (30% of total), while ramping up energy efficiency.A particularly instructive example is Amazon. In 2019 the company established a 2040 net zero target which was then verified by the UN Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) which has been leading the charge in getting companies to establish climate targets compatible with the Paris agreement. But over the next four years Amazon’s emissions went up by 40%. Given this dismal performance, the SBTi was forced to act and removed Amazon and over 200 companies from its Corporate Net Zero Standard. This is also not surprising given that net zero and even the Paris agreement have been built around the perceived need to keep burning fossil fuels, at least in the short term. Not to do so would threaten economic growth, given that fossil fuels still supply over 80% of total global energy. The trillions of dollars of fossil fuel assets at risk with rapid decarbonisation have also served as powerful brakes on climate action.

Overshoot: The way to understand this doublethink: that we can avoid dangerous climate change while continuing to burn fossil fuels – is that it relies on the concept of overshoot. The promise is that we can overshoot past any amount of warming, with the deployment of planetary-scale carbon dioxide removal dragging temperatures back down by the end of the century. This not only cripples any attempt to limit warming to 1.5°C, but risks catastrophic levels of climate change as it locks us in to energy and material-intensive solutions which for the most part exist only on paper. To argue that we can safely overshoot 1.5°C, or any amount of warming, is saying the quiet bit out loud: we simply don’t care about the increasing amount of suffering and deaths that will be caused while the recovery is worked on. The way to understand this doublethink: that we can avoid dangerous climate change while continuing to burn fossil fuels – is that it relies on the concept of overshoot. The promise is that we can overshoot past any amount of warming, with the deployment of planetary-scale carbon dioxide removal dragging temperatures back down by the end of the century. This not only cripples any attempt to limit warming to 1.5°C, but risks catastrophic levels of climate change as it locks us in to energy and material-intensive solutions which for the most part exist only on paper. To argue that we can safely overshoot 1.5°C, or any amount of warming, is saying the quiet bit out loud: we simply don’t care about the increasing amount of suffering and deaths that will be caused while the recovery is worked on. Read more here

AND THEN YOU GET TO: 30 May 2024, The Conversation: Sleight of hand: Australia’s Net Zero target is being lost in accounting tricks, offsets and more gas.In announcing Australia’s support for fossil gas all the way to 2050 and beyond, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has pushed his government’s commitment to net zero even further out of reach. When we published our analysis in December on Climate Action Tracker, a global assessment of government climate action, we warned Australia was unlikely to achieve its net zero target, and rated its efforts as “poor.”…  The land sleight of hand Because we have very few real emissions policies, our emissions in many sectors are actually rising. The best way to understand this trend is to remove the energy and land use sectors, so we can clearly see how much other areas are rising. When you do, the data shows Australia’s emissions jumped by 3% from 2022 to 2023 and are now 11% above 2005 levels, with the largest growth from transport. Yet just as the Coalition did, our current government says emissions are dropping. How can this be? Yes, energy emissions are dropping. But the real rub is in the famously malleable land use change and forestry sector. This area is the only sector which can act as either a carbon sink or carbon source. If forests are regrowing fast, the sector acts as a sink, offsetting emissions from elsewhere.Our own calculations show that successive governments have kept increasing their projections for how much carbon they believe the land use sector is storing. That’s happened every year since 2018. If you keep changing how big a carbon sink land use is, you seem to make the task of cutting emissions a lot easier. The topline figure of a 25% fall in emissions sounds great. But in reality, there’s been very little change, if we avoid land use. The Albanese government has now repeatedly changed how it calculates how much carbon the land sector is storing, as well as future projections. Between the end of 2021 and 2023, the government’s figures changed markedly. Land use as a way to capture carbon soared, from 16 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year to a whopping 88 megatonnes a year as of 2022. This is a staggering 17% of Australia’s 2022 fossil fuel and industry emissions. By changing these projections, our national emissions over 2022-23 magically appear to have fallen 6% in a year. Every time the government recalculates how much carbon the land use sector is storing, the less work it has to do on actually cutting emissions from fossil fuels and industry sectors. That means it only needs emissions from fossil fuel use, industry, agriculture and waste to fall 24% by 2030, rather than 32%. These changes to land use accounting may sound arcane, but they have very real consequences.

The land sleight of hand Because we have very few real emissions policies, our emissions in many sectors are actually rising. The best way to understand this trend is to remove the energy and land use sectors, so we can clearly see how much other areas are rising. When you do, the data shows Australia’s emissions jumped by 3% from 2022 to 2023 and are now 11% above 2005 levels, with the largest growth from transport. Yet just as the Coalition did, our current government says emissions are dropping. How can this be? Yes, energy emissions are dropping. But the real rub is in the famously malleable land use change and forestry sector. This area is the only sector which can act as either a carbon sink or carbon source. If forests are regrowing fast, the sector acts as a sink, offsetting emissions from elsewhere.Our own calculations show that successive governments have kept increasing their projections for how much carbon they believe the land use sector is storing. That’s happened every year since 2018. If you keep changing how big a carbon sink land use is, you seem to make the task of cutting emissions a lot easier. The topline figure of a 25% fall in emissions sounds great. But in reality, there’s been very little change, if we avoid land use. The Albanese government has now repeatedly changed how it calculates how much carbon the land sector is storing, as well as future projections. Between the end of 2021 and 2023, the government’s figures changed markedly. Land use as a way to capture carbon soared, from 16 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year to a whopping 88 megatonnes a year as of 2022. This is a staggering 17% of Australia’s 2022 fossil fuel and industry emissions. By changing these projections, our national emissions over 2022-23 magically appear to have fallen 6% in a year. Every time the government recalculates how much carbon the land use sector is storing, the less work it has to do on actually cutting emissions from fossil fuels and industry sectors. That means it only needs emissions from fossil fuel use, industry, agriculture and waste to fall 24% by 2030, rather than 32%. These changes to land use accounting may sound arcane, but they have very real consequences.

No credible pathway – The only pathway we have left to limit warming to 1.5°C is political. Leaders must take up their responsibility to actually act and develop measures to rapidly cut carbon emissions.Cutting emissions means not emitting them. Relying on offsets or changing how much we think the land is absorbing is not enough. Sadly, our current government seems set on a sleight of hand. Rather than cutting fossil fuel and industry emissions 50% or more by 2030, as it should, the Australian government’s changes to land use accounting mean it has to do much less.This is not a credible pathway towards net zero. READ MORE HERE

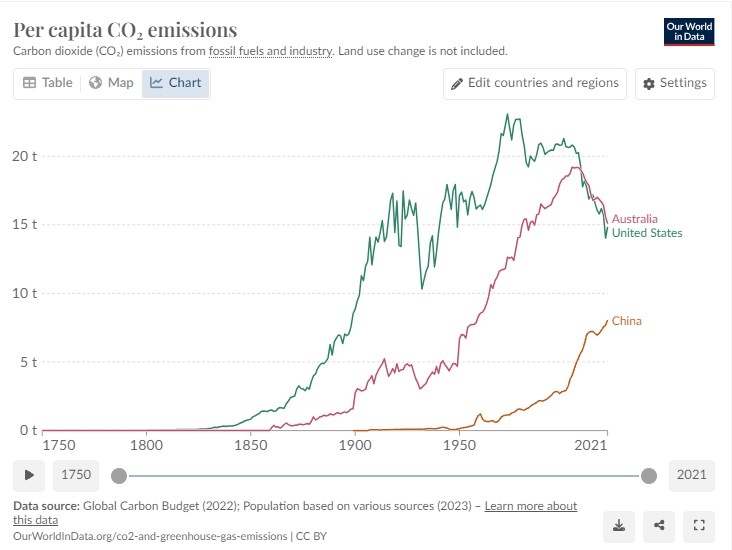

Australia: Per capita: how much CO2 does the average person emit?

This interactive chart shows how much carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced in a given year.

This interactive chart shows how much carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced in a given year.

A few points to keep in mind when considering this data:

- These figures are based on ‘production’ or ‘territorial’ emissions (i.e. emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, or cement production within a country’s borders). It does not consider the emissions of traded goods (consumption-based emissions). You find consumption-based emissions later in this country profile.

- These figures look specifically at CO2 emissions – not total greenhouse gas emissions. You find total, and other greenhouse gas emissions, later in this country profile.

- Annual emissions can be largely influenced by population size – we present the per capita figures above.

- ACCESS WEBSITE HERE

First steps of a new government – let’s see what they can do

3 November 2022, The Conversation: Australia relies on controversial offsets to meet climate change targets. We might not get away with it in Egypt. It’s small wonder a major fossil fuel producer like Australia has relied so heavily on carbon offsets. Plant new forests – or say you will avoid clearing old ones – and you can keep approving new gas and coal developments. This year, whistleblower Professor Andrew McIntosh claimed up to 80% of these offsets weren’t real. They didn’t actually offset emissions. In Australia, renewables are the only real source of emission reduction. The rest of the economy is set to slowly increase emissions. But what matters is actually reducing how many tonnes of heat-trapping greenhouse gases go up into the sky and add to the 2.5 trillion tonnes of CO2 humans have already emitted – of which more than a trillion tonnes remain in the atmosphere. Last year, carbon dioxide and methane levels hit new highs. Offsets measure how much carbon is soaked up by, say, a reforestation project. As the saplings grow, they store carbon. Offsets are a way to theoretically package up this stored carbon – or emissions claimed to have been avoided by not deforesting an area of land – and sell it to companies who would like to keep pumping out emissions equal to the amount stored in new forests. You can quickly see the problem. Who’s checking to see if these forests were planted – or if they were going to be planted anyway? Are emission reductions or storage real – and additional to what would otherwise have happened? Read more here

24 May 2022, Renew Economy: Albanese commits Australia to stronger 2030 target, starts climate reset. Prime minister Anthony Albanese has commenced a reset of Australia’s international climate action commitments, formalising its commitment to a stronger 2030 reduction target in his first address to a major international forum. Just a day after being sworn in, Albanese is in Tokyo for the ‘Quad’ meeting with the leaders of Japan, India and the United States to discuss collaboration between the four regional powers and how they can rebuild relationships across the Pacific region. Albanese used his opening address to formally commit Australia to the stronger 2030 emissions reduction target that Labor had taken to the election, saying that delivering climate action was a key diplomatic challenge in the Indo-Pacific region. “The region is looking to us to work with them and to lead by example. That’s why my government will take ambitious action on climate change and increase our support to partners in the region as they work to address it, including with new finance,” Albanese told the meeting. “We will act in recognition that climate change is the main economic and security challenge for the island countries of the Pacific. Under my government, Australia will set a new target to reduce emissions by 43 per cent by 2030, putting us on track for net zero by 2050.” It represents the first time since the Abbott government in 2015 that Australia has committed to increasing its 2030 emissions reduction target. The outgoing Morrison government had held firm to Abbott’s 26 to 28 per cent reduction target – a goal long seen as inadequate both domestically and among Australia’s international peers. Read more here

Your G7 greenwashing guide: How Australia will feign climate ambition

9 June 2021, Renew Economy: This week, prime minister Scott Morrison will be reconnecting with a topic he has been struggling to disconnect from entirely: the problem of climate change. This happens mostly through a single frame: presenting Australia’s current inaction on climate change as if it is true ambition. The story, of course, is pretty ugly. Australia’s emissions have been rising for some time, tempered partially by the growth of renewable energy, but accelerated by a bloated and emissions intensive gas industry and by highly-polluting transport. Buildings, industry, agriculture and other mining remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels. The overall picture: the government is relying on vestigial policies from a previous government and the impacts of a deadly pandemic to do all the work on climate.

Today, Scott Morrison will reportedly say in a speech ahead of the G7 that Australia is deploying renewables “three times faster than the USA, China and the EU”. It’s a vague claim that is impossible to verify, but it is also a classic example of the greenwashing of Australia’s fossil fuel problem. This year, the primary mission of saving face has been trying to twist Australia’s climate and energy data in incredibly silly ways, such that is resembles climate ambition. I have tracked it closely, because it certainly seems like one of the most important stories on climate in Australia this year. The first instance was the election campaign of Australia’s former finance minister and now successful new Secretary-General of the Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Mathias Cormann. He carried around a colour coded spreadsheet that has never been publicly shared, but that we can comfortably assume was not a fair representation of climate action, given it showed that “Australia’s performance stood up well against some other [OECD] members”. Read more here NOTE: Tactics remain the same no matter what conference/summit, is attended.

Australia drops plan to use Kyoto credits to meet Paris climate target – do they mean it??

5 December 2020, SMH: Prime Minister Scott Morrison will tell world leaders that Australia has abandoned a longstanding plan to use Kyoto carryover credits to achieve its emissions reduction targets, in a pledge that paves the way for a reset of his government’s climate change policies. The decision to drop the controversial Kyoto credits will be announced at a December 12 summit convened by British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who has asked leaders for “ambitious” new commitments as a condition of speaking at the gathering. (ED: but he wasn’t invited? Does it still count?)

Mr Morrison’s promise to reach Australia’s 2030 target without using carryover credits is likely to be welcomed by other countries that have long criticised the accounting method, building goodwill for the Australian position going into the Glasgow summit. The Prime Minister hinted on Thursday the government might not need to use the credits, telling Parliament he had “kept commitments and beaten commitments” in the past and would outline this in his speech to the British gathering. Read more here

Still they will not let go!

4 March 2020, Climate Home News, Australia’s carbon accounting plan for Paris goals criticised as ‘legally baseless’. Legal experts wrote to Prime Minister Scott Morrison warning the use of old carbon credits to meet the country’s 2030 goals would set a ‘dangerous precedent’. Australia’s plan to use Kyoto-era carbon credits to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement is inconsistent with international law, legal experts have warned. In a letter to Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, nine international and climate law professors said Australia’s method would set “a dangerous precedent” for other countries to “exploit loopholes or reserve their right not to comply with the Paris Agreement”. “Our considered view is that the proposed use of these ‘Kyoto credits’ to meet targets under the Paris Agreement is legally baseless at international law,” the letter read. Australia is one of the only countries in the world to have explicitly said it would carry over Kyoto-era carbon credits as a means to meet its 2030 climate target. The credits were initially issued for Australia’s overachievement in meeting its 1997 Kyoto pledge to curb emissions by 2012. Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, Australia has pledged to cut emissions by at least 26% from 2005 levels by 2030. Morrison told the UN in September 2019 that “Australia will meet our Paris commitments”, and called the goals “a credible, fair, responsible and achievable contribution to global climate change action.” But a 2019 UN Environment report listed Australia among a group of 20 nations requiring “further action” to meet its Paris target, along with Brazil, Canada, Japan, South Korea, South Africa and the United States. Read more here

AND STILL IT CONTINUES! Oz Govt playing with dodgy accounting to achieve its target, can they be stopped?

17 December 2019, Renew Economy, Why the battle over ‘Kyoto carryover’ is such a big deal for the climate? As delegates from the COP25 UN climate talks make their way home, many will be considering how it could be possible to resolve one of the core sticking  points for negotiators could be resolved in time for the next round of talks in Glasgow. Much of the battles between negotiators in Madrid focused on the issue of surplus emissions permits leftover from the Kyoto protocol. As the global climate governance is set to transition from the constrained Kyoto Protocol into the all encompassing Paris Agreement, a small group of countries, including Australia, China, India the United States and Brazil, fought to protect their favourable position, created under the Kyoto Protocol through soft targets and convenient accounting loopholes. Australia neither succeeded in securing agreement at the UN talks to allow for surplus Kyoto-era units to be carried over into the Paris Agreement nor was Australia prevented from doing so. In failing to reach an agreement in Madrid, negotiators will reconsider the issue at the next round of talks to be held in Glasgow in late 2020. The level of attention given to the issue, and the resulting frustration expressed by negotiators on both sides, reflects the scale of emissions reductions that could be put as risk if countries conceded to the demands that surplus Kyoto units be carried over into the Paris Agreement. Read more here

points for negotiators could be resolved in time for the next round of talks in Glasgow. Much of the battles between negotiators in Madrid focused on the issue of surplus emissions permits leftover from the Kyoto protocol. As the global climate governance is set to transition from the constrained Kyoto Protocol into the all encompassing Paris Agreement, a small group of countries, including Australia, China, India the United States and Brazil, fought to protect their favourable position, created under the Kyoto Protocol through soft targets and convenient accounting loopholes. Australia neither succeeded in securing agreement at the UN talks to allow for surplus Kyoto-era units to be carried over into the Paris Agreement nor was Australia prevented from doing so. In failing to reach an agreement in Madrid, negotiators will reconsider the issue at the next round of talks to be held in Glasgow in late 2020. The level of attention given to the issue, and the resulting frustration expressed by negotiators on both sides, reflects the scale of emissions reductions that could be put as risk if countries conceded to the demands that surplus Kyoto units be carried over into the Paris Agreement. Read more here

For more background as to how all this came about read on… Kyoto Credits: as Australia cooks, the Coalition cooks the books

Australia is counting on cooking the books to meet its climate targets

31 January 2019, Conversation, A new OECD report has warned that Australia risks falling short of its 2030 emissions target unless it implements “a major effort to move to a low-carbon model”. This view is consistent both with official government projections released late last year, and independent analysis of Australia’s emissions trajectory. Yet the government still insists we are on track, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison claiming as recently as November that the 2030 target will be reached “in a canter”. What’s really going on? Does the government have any data or modelling to serve as a basis for Morrison’s confidence? And if so, why doesn’t it tell us? …. To reach our Paris target, the government estimates that we will need to reduce emissions by the equivalent of 697 million tonnes of carbon dioxide before 2030. It also calculates that the overdelivery on previous climate targets already represents a saving of 367Mt, and that low economic demand would save a further 571Mt. That adds up to 938Mt of emissions reductions, outperforming the target by 35% – a canter that would barely work up a sweat. Read more here

Australia on track to miss Paris climate targets as emissions hit record highs

14 September 2018, The Guardian, NDEVR Environmental data suggests Australia will miss targets by 1bn tonnes of carbon dioxide under current trajectory. Australia remains on track to miss its Paris climate targets as carbon emissions continue to soar, according to new data. The figures from NDEVR Environmental for the year up to the end of June 2018 show the country’s emissions were again the highest on record when unreliable data from the land use and forestry sectors was excluded. It is the third consecutive year for record-breaking emissions. Read more here

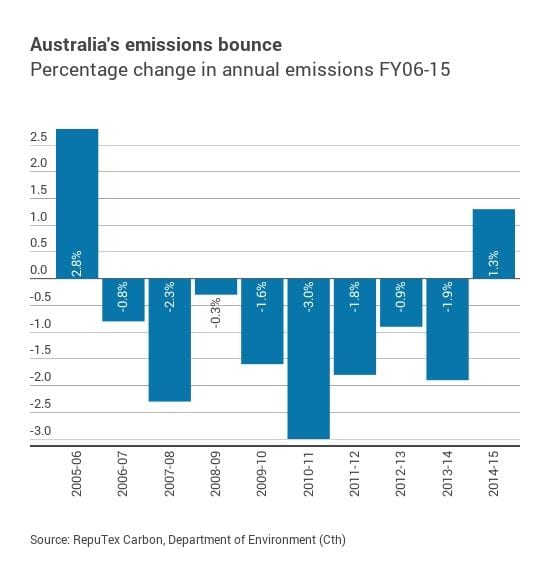

Gas boom fuels Australia’s third straight year of rising emissions

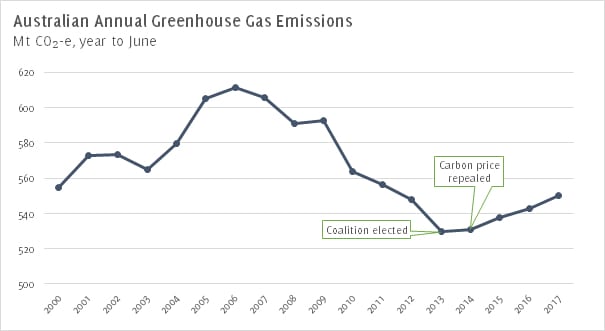

14 May 2018, The Guardian, Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions continue to soar, increasing for the third consecutive year according to new data published by the Department of Environment and Energy. The Turnbull government published new quarterly emissions data late on Friday which reveals Australia’s climate pollution increased by 1.5% in the year to December 2017. The expansion in LNG exports and production is identified as the major contributor to the increase, but the data shows a jump in emissions across all sectors – including waste, agriculture and transport – except for electricity, the one area that recorded a decrease in emissions. In particular, the department’s data shows a 10.5% increase in fugitive emissions from the production, processing, transport, storage, transmission and distribution of fossil fuels such as coal, crude oil and natural gas, driven by an increase of 17.6% in natural gas production. It comes at a time when the government has been pressuring states and territories to lift bans on fracking for new unconventional gas development and just weeks after the Northern Territory announced it would end its ban on fracking. Publication of the data also comes after Australia recorded its hottest and driest April in 21 years. Between 2007 and 2013, under the previous federal government, carbon pollution declined by more than 11%. The Australian Conservation Foundation said on Monday it was embarrassing that a developed country such as Australia was recording rising climate pollution, and the Turnbull government was failing on climate policy. “This data confirms pollution is rising from transport, industry and gas production because there is no plan from Canberra to replace burning polluting coal, oil and gas with clean energy,” the ACF’s Gavan McFadzean said. “The federal budget contained no new money to incentivise industry and landowners to clean-up their act. The Climate Change Authority will be worse off to the tune of $550,000. Yet there is money for miners: the diesel fuel rebate remains in place.”The organisation also questioned why the government was years behind markets such as the United States and Canada in the introduction of tougher pollution standards for vehicles. Read more here

14 May 2018, The Guardian, Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions continue to soar, increasing for the third consecutive year according to new data published by the Department of Environment and Energy. The Turnbull government published new quarterly emissions data late on Friday which reveals Australia’s climate pollution increased by 1.5% in the year to December 2017. The expansion in LNG exports and production is identified as the major contributor to the increase, but the data shows a jump in emissions across all sectors – including waste, agriculture and transport – except for electricity, the one area that recorded a decrease in emissions. In particular, the department’s data shows a 10.5% increase in fugitive emissions from the production, processing, transport, storage, transmission and distribution of fossil fuels such as coal, crude oil and natural gas, driven by an increase of 17.6% in natural gas production. It comes at a time when the government has been pressuring states and territories to lift bans on fracking for new unconventional gas development and just weeks after the Northern Territory announced it would end its ban on fracking. Publication of the data also comes after Australia recorded its hottest and driest April in 21 years. Between 2007 and 2013, under the previous federal government, carbon pollution declined by more than 11%. The Australian Conservation Foundation said on Monday it was embarrassing that a developed country such as Australia was recording rising climate pollution, and the Turnbull government was failing on climate policy. “This data confirms pollution is rising from transport, industry and gas production because there is no plan from Canberra to replace burning polluting coal, oil and gas with clean energy,” the ACF’s Gavan McFadzean said. “The federal budget contained no new money to incentivise industry and landowners to clean-up their act. The Climate Change Authority will be worse off to the tune of $550,000. Yet there is money for miners: the diesel fuel rebate remains in place.”The organisation also questioned why the government was years behind markets such as the United States and Canada in the introduction of tougher pollution standards for vehicles. Read more here

Forget Paris: Australia needs to stop pretending we’re tackling climate change

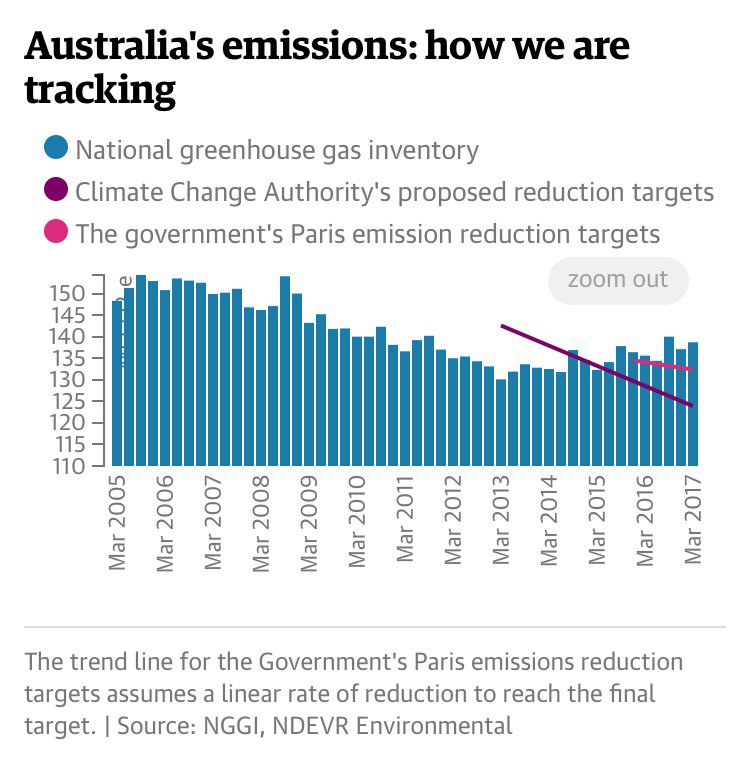

11 January 2018, ABC News – Science: As the Bureau of Meteorology confirms another record-breaking year for temperatures in Australia, we should expect a sense of urgency to be creeping into Australia’s climate policy. Instead, we’re seeing the opposite. While 2015-17 were all within the hottest six years on record, our carbon emissions also continued to increase during the same period, including an all-time peak in 2017, when unreliable land-use data was excluded from the analysis. This is despite signing up to the Paris Agreement in 2015, which outlined a plan to reduce our carbon emissions by 26-28 per cent by 2030. Government data pushed out under the cloak of Christmas indicates that we will be about 140 million tonnes — or about 30 per cent — above that target based on current growth. And this is under the prime ministership of Malcolm Turnbull, who in 2010 warned that “the consequences of unchecked global warming would be catastrophic.” At the time, he argued that effective action on climate change required moving to “zero, or very near zero emissions [energy] sources. “The science tells us that we have already exceeded the safe upper limit for atmospheric carbon dioxide.” The aim of the Paris Agreement is to keep global temperature increase to “well below” 2 degrees, and to attempt to achieve a limit of 1.5 degrees warming above pre-industrial levels. Last year averaged 0.95 of a degree above Australia’s long-term average….

For Australia’s part, getting anywhere near our Paris targets means tackling our key emissions sources — electricity, transport, industry and agriculture, and reversing alarming deforestation trends. Forests act as invaluable carbon sinks, yet in Queensland alone in 2015-16, 395,000 hectares of forest were cleared following the relaxation of land clearing laws under the Newman LNP government. That number is feared to hit around a million hectares based on estimates from Queensland’s self-assessment data, putting that state on par with Brazil. And unreliable data on land clearing emissions mean we may actually be underestimating our carbon footprint.

For Australia’s part, getting anywhere near our Paris targets means tackling our key emissions sources — electricity, transport, industry and agriculture, and reversing alarming deforestation trends. Forests act as invaluable carbon sinks, yet in Queensland alone in 2015-16, 395,000 hectares of forest were cleared following the relaxation of land clearing laws under the Newman LNP government. That number is feared to hit around a million hectares based on estimates from Queensland’s self-assessment data, putting that state on par with Brazil. And unreliable data on land clearing emissions mean we may actually be underestimating our carbon footprint.

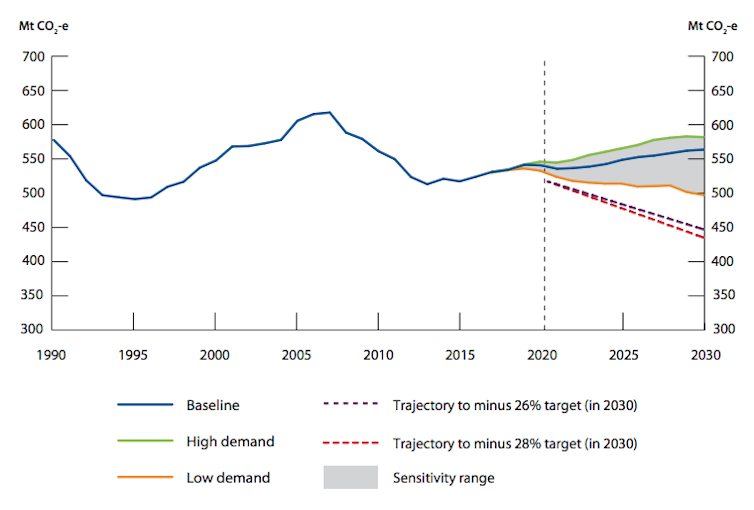

Government optimism at odds with UN: Despite last financial year’s continued emissions growth, Environment and Energy Minister Josh Frydenberg remains upbeat about Australia’s commitment to the Paris Agreement. “If you look on a yearly basis that is true [that emissions went up]. But if you look on the last quarter, they went down. If you look at the trend, it is improving. And when you talk about the 2030 target, which is our Paris commitment, the numbers that were most recently shown, indicate that they were 30 per cent better than when Labor were last in office,” the Minister told RN Breakfast. But his optimism is at odds with a number of experts, and is contrary to what was reported in the United Nations Emissions Gap Report (see below), 2017. “Government projections indicate that emissions are expected to reach 592 [million tonnes] in 2030, in contrast to the targeted range of 429-440 [million tonnes],” the report states.

The Emissions Gap Report 2017 A UN Environment Synthesis Report – November 2017 (extracts)

PAGE 8: In accordance with the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules, Australia uses a carbon budget approach that accounts for cumulative emissions over the 2013–2020 period in order to assess progress towards its pledge. Australia’s latest official projections find that for the budget period (2013–2020), Australia is now on track to overachieve its 2020 pledge by 97 MtCO2 e (cumulative), excluding a 128 MtCO2 e carry-over from its first commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol (Government of Australia, 2016). Independent studies consider the year 2020 in isolation, and find a difference of about 63 MtCO2 e between Australia’s projected 2020 emissions and its pledge level for that year (Kuramochi et al., 2016b; PBL, 2017; Reputex, 2016), which is higher than the 37 MtCO2 e difference of Australia’s latest official projections (Government of Australia, 2016). The former do not factor in the most recent official projections.

PAGE 23: Australia committed to a 26–28 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 below 2005 levels, including LULUCF. Government projections indicate that emissions are expected to reach 592 MtCO2 e/year in 2030 (Government of Australia, 2016), in contrast to the targeted range of 429-440 MtCO2 e/year. Independent analyses (Kuramochi et al., 2016; Reputex, 2016) confirm that the emissions are set to far exceed its Paris Agreement NDC target for 2030. The Emissions Reduction Fund, which the Government of Australia considers to be a key policy measure to reduce emissions alongside other measures such as the National Energy Productivity Plan and targets for the reduction of hydrofluorocarbons (85 percent by 2036), does not set Australia on a path to meeting its targets.

PAGE 44: 5.3.1. Australia: coal exports and policy challenges In Australia, which has relied heavily on its abundant coal reserves for domestic electricity production, transitioning away from coal is likely to pose significant policy challenges. It is widely anticipated that the number of coal-fired power plants will continue to decline, as plants come towards the end of their planned lifetimes. A number of older coal-fired power plants have been shut down, and new coal-fired capacity is now widely seen as ‘uninvestable’ by the private sector, due to carbon risks and because renewable energy is rapidly gaining a cost advantage (Morgan 2017). Being the world’s second largest coal exporter, the even bigger question is the future of coal exports. Thermal coal exports, which are directly dependent on other countries’ climate change policies, currently stand at around 200 million tonnes per year (Australian Government 2017), almost double the volume from a decade ago. Large-scale expansion of coal mining for export from inland areas of north-eastern Australia is under discussion. There is currently no policy to accelerate the phase-out of coal in domestic use, and no systematic framework to ease the transition away from coal in regions where large coal-based infrastructure exists, or where coal is mined. Australia’s experience with climate policy has been a difficult one, with the issue heavily politicized, and emission reduction policy instruments the subject of political contest. Australia is the only country that introduced a full-scale carbon pricing scheme (in 2012) and then abolished it (in 2014). Policy uncertainty is deep-seated in the energy sector, stifling investment (Jotzo, Jordan, and Fabian 2012).

19 December 2017, Renew Economy, Turnbull’s big climate fail, and no positive change in policy. The Turnbull government has declared its climate policies a success, in a self-generated review released alongside data revealing yet another rise in the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions – and no plans to do anything to reverse the “shameful and embarrassing” trend. In a statement on Tuesday accompanying the federal government’s 2017 Review of Climate Change Policies, environment minister Josh Frydenberg said the report showed the Coalition’s “economically responsible” approach to meeting its international climate commitments was working as planned. “The climate review found that …Australia is playing its part on the world stage through bilateral and multi‑lateral initiatives and the ratification of the Paris Agreement to reduce our emissions by 26 to 28 per cent on 2005 levels by 2030,” he said. And indeed it does; declaring on page 6 that “we will meet our 2030 target and we will do so without compromising economic growth or jobs. Our current policy suite can deliver this outcome.” Read More here

19 December 2017, Renew Economy, Turnbull’s big climate fail, and no positive change in policy. The Turnbull government has declared its climate policies a success, in a self-generated review released alongside data revealing yet another rise in the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions – and no plans to do anything to reverse the “shameful and embarrassing” trend. In a statement on Tuesday accompanying the federal government’s 2017 Review of Climate Change Policies, environment minister Josh Frydenberg said the report showed the Coalition’s “economically responsible” approach to meeting its international climate commitments was working as planned. “The climate review found that …Australia is playing its part on the world stage through bilateral and multi‑lateral initiatives and the ratification of the Paris Agreement to reduce our emissions by 26 to 28 per cent on 2005 levels by 2030,” he said. And indeed it does; declaring on page 6 that “we will meet our 2030 target and we will do so without compromising economic growth or jobs. Our current policy suite can deliver this outcome.” Read More here

Australia & Turkey only developed nations breaking emissions records

28 September 2017, Australian Institute, Climate outliers: Australia and Turkey the only developed nations breaking emissions records. The Australia Institute’s new Climate & Energy Program has released the National Energy Emissions Audit. The Audit, compiled by renowned energy specialist Dr Hugh Saddler, provides a comprehensive, up-to-date indication of key greenhouse gas and energy trends in Australia. “The report finds, disturbingly, that Australia’s annual emissions from energy use have increased to their highest ever level, higher than the previous peak seen eight years ago, in 2009,” Dr Saddler said. “Australia’s failure to invest in efficient transport infrastructure, such as rail, has led to emissions from transport fuels continuing to grow, again, unlike the rest of the developed world. “The continued rise in fuel emissions demonstrates why requiring a reduction for the electricity sector that is only equal to the Paris target would likely see Australia fail to meet its international commitment,” Dr Saddler said. Key findings:

- Australia’s energy emissions continue to increase, breaking all-time record

- Among developed nations, only Australia and Turkey are breaking emissions records

- Petroleum, in particular diesel consumption is the main driver of emission increases

- There is no indication of when or if growth in petroleum emissions will stop Read More here

Turnbull’s new energy target: Drop the “clean” and ignore climate

States leading the way to a renewable future

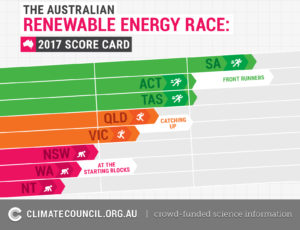

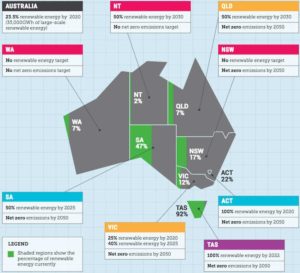

31 August 2017, Climate Council Report, States and territories are the driving force behind Australia’s transition to clean, affordable and efficient renewable energy and storage technology, our new report has found. The ‘Renewables Ready: States Leading the Charge,’ report shows South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory are all leading the renewables race, while the Federal Government remains stuck at the starting block. KEY FINDINGS:

31 August 2017, Climate Council Report, States and territories are the driving force behind Australia’s transition to clean, affordable and efficient renewable energy and storage technology, our new report has found. The ‘Renewables Ready: States Leading the Charge,’ report shows South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory are all leading the renewables race, while the Federal Government remains stuck at the starting block. KEY FINDINGS:

- In the absence of national energy and climate policy, all states and territories (except Western Australia) now have strong renewable energy targets and/or net zero emissions targets in place.

- State and territory targets and announced coal closures are expected to deliver Australia’s 2030 emissions reduction target of 26-28% reduction on 2005 levels.

- TAS, SA and the ACT continue to lead on percentage renewable electricity, and have the most renewable energy capacity per capita (excluding large-hydro).

- NSW and QLD are set for a dramatic increase in renewable energy with the greatest capacity and number (respectively) of projects under construction in 2017.

- Households in QLD, SA and WA continue to lead in the proportion of homes with rooftop solar.

- SA is building the world’s largest lithium ion battery storage facility.

Finally, release of Oz emissions for 2016

11 July 2017, The Guardian, No wonder the government tries to hide its emissions reports. They stink. Last Friday, the Australian government finally released the latest greenhouse gas emissions report, showing emissions have risen in the past year. When excluding emissions from land use, 2016 saw Australia release a record level of CO2 into the atmosphere. It confirms the failure of the government’s environmental policy at a time when electricity prices – despite the absence of a carbon price – continue to rise at levels above inflation. The government has a history of being scared to release the greenhouse gas reports. Last year it released the March 2016 and June 2016 reports on the Thursday before Christmas – not exactly peak viewing time. It also meant the March report was released nine months after the March quarter had actually finished. And once again the government held off releasing the latest report. But in a level of coincidence equal to that of Bill Heslop running into Deirdre Chambers in the Porpoise Split Chinese restaurant, on the day that the Australian Conservation Foundation released FOI documents showing that the government had been sitting on the report for more than a month, the government released the latest report. And in an effort that rather stretches the meaning of “quarterly”, the government “incorporated” the September quarter figures into the December report. It says something about how poorly this government values the issue of climate change that over a month ago we had the figures on the entire production that occurred in Australia during the first three months of this year, and yet here we are in July and we still only know the level of greenhouse gas emissions up to December last year. The figures in the report quickly made it obvious why the government has held off releasing them. They stink. And as every report since June 2014 has shown, the end of the carbon price has led to an increase in emissions. The poor departmental officials try to paint a happy picture. The release leads with the line that “total emissions for Australia for the year to December 2016 (including Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry) are estimated to be 543.3 Mt CO2-e.” They note that this is 2.0% below emissions in 2000, and 10.2% below emissions in 2005. Oddly, they don’t note that is it 1.0% above the emissions in 2015. The inclusion of land use, land use change and forestry is a fairly dodgy measure. Read More here

11 July 2017, The Guardian, No wonder the government tries to hide its emissions reports. They stink. Last Friday, the Australian government finally released the latest greenhouse gas emissions report, showing emissions have risen in the past year. When excluding emissions from land use, 2016 saw Australia release a record level of CO2 into the atmosphere. It confirms the failure of the government’s environmental policy at a time when electricity prices – despite the absence of a carbon price – continue to rise at levels above inflation. The government has a history of being scared to release the greenhouse gas reports. Last year it released the March 2016 and June 2016 reports on the Thursday before Christmas – not exactly peak viewing time. It also meant the March report was released nine months after the March quarter had actually finished. And once again the government held off releasing the latest report. But in a level of coincidence equal to that of Bill Heslop running into Deirdre Chambers in the Porpoise Split Chinese restaurant, on the day that the Australian Conservation Foundation released FOI documents showing that the government had been sitting on the report for more than a month, the government released the latest report. And in an effort that rather stretches the meaning of “quarterly”, the government “incorporated” the September quarter figures into the December report. It says something about how poorly this government values the issue of climate change that over a month ago we had the figures on the entire production that occurred in Australia during the first three months of this year, and yet here we are in July and we still only know the level of greenhouse gas emissions up to December last year. The figures in the report quickly made it obvious why the government has held off releasing them. They stink. And as every report since June 2014 has shown, the end of the carbon price has led to an increase in emissions. The poor departmental officials try to paint a happy picture. The release leads with the line that “total emissions for Australia for the year to December 2016 (including Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry) are estimated to be 543.3 Mt CO2-e.” They note that this is 2.0% below emissions in 2000, and 10.2% below emissions in 2005. Oddly, they don’t note that is it 1.0% above the emissions in 2015. The inclusion of land use, land use change and forestry is a fairly dodgy measure. Read More here

13 June 2017, Climate Council, On Friday, Australia’s Chief Scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, released the findings of a review into the future of the National Electricity Market. The Finkel Review was tasked with developing a “blueprint” for the national electricity market (NEM) that:

13 June 2017, Climate Council, On Friday, Australia’s Chief Scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, released the findings of a review into the future of the National Electricity Market. The Finkel Review was tasked with developing a “blueprint” for the national electricity market (NEM) that:

- delivers on Australia’s emissions reduction commitments

- provides affordable electricity, and

- ensures a high level of security and reliability.

- It’s a hefty 212 page document so the Climate Council has put together an explainer to help unpack the content.

Access report by clicking on image

June 2017, Australia Institute National Energy Emissions Audit. Providing a comprehensive, up-to-date

indication of key greenhouse gas and energy trends in Australia. Access Report here

Oz emissions rise in off-season

8 June 2017, The Guardian, Australia’s carbon emissions rise in off-season for first time in a decade. Exclusive: On the eve of the long-awaited Finkel review, analysis shows Australia’s emissions rose sharply in the first quarter of 2017. Australia’s carbon emissions jumped at the start of 2017, the first time they have risen in the first few months of a year for more than a decade, according to projections produced exclusively for the Guardian. Emissions in the first three months of the year normally drop compared with the previous quarter, driven by seasonal factors and holidays. But in something not seen in since 2005, emissions rose in the first quarter of 2017 compared with the last quarter of 2016 by 1.54m tonnes of CO2, according to the study by consultants NDEVR Environmental. The rise was driven by increases in emissions from electricity generation. Government data on greenhouse gas emissions is released up to a full nine months after the end of a quarter. So NDEVR Environmental replicate the government data for the Guardian, releasing it about a month after the quarter finishes. The unseasonal rise in emissions continues a trend of rising national emissions which began in 2014 and which the government’s own modelling suggests will continue for decades to come, based on current policies. Read More here

Budget silence on climate policy

11 May 2017, Renew Economy, Budget papers reveal jobs to grow at CEFC, but CCA left without funds. While the Turnbull government’s second budget distinguished itself for its complete lack of provisions for – or even references to – climate change, Renew Economy did notice that the papers flagged an increase in staff numbers at the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, from 80 people to 101. According to the CEFC, the staff increase noted in the budget reflects the green bank’s expectation that it will need more hands on deck to manage its “expanding and diversified” investment portfolio. And that’s because it is doing very well. “The budget papers show that we are forecast to exceed the target $800 million to $1 billion of new contracted investments during 2016/17, which is a considerable step up in the level of investment over prior periods,” a CEFC spokesperson told RE in an email. “As the CEFC’s investment portfolio progressively grows (currently $1.5 billion invested and $3 billion committed of the $10 billion appropriated to CEFC), the Board of the CEFC must ensure it has the requisite resources in place to properly manage those investments and associated business risks, on behalf of the Australian taxpayer, in an efficient and effective manner,” the email said. The extra funds contrasts with the fate of the Climate Change Authority, which has been effectively defenestrated by the Coalition government. Once again, its funding does not extend beyond the coming financial year, as the Coalition repeats its desire to close the authority. The CCA, established by Labor and the Greens to provide independent advice on climate targets and policies, has been embroiled in controversy in recent months, leading to resignations from key board members such as Clive Hamilton and John Quiggin, over what they described as compromised reports. But even these have been ignored by the Coalition. The CEFC has also been on the coalition’s hit list, but is now tolerate given it has chalked up an impressive track record since its inception in 2013. The LNP has shifted from describing the CEFC as a “giant green hedge fund” or “honeypot to every white-shoe salesman imaginable,” to claiming it as a major national success; one that marked its third year of operation with a record $837 million committed to new clean energy investments, contributing to projects with a total value of $2.5 billion, and achieving a 73 per cent year-on-year increase in the value of new investment commitments. Read more here

10 May 2017, Renew Economy, Turnbull abandons fig leaf and stands naked on climate policy. You would think that with all the hoo-ha about the scandalous increases in electricity prices that it would have rated some sort of mention in the budget. You know, one of the biggest cost inputs for business being addressed in the government’s economic centrepiece. But no. The 2nd Morrison/Turnbull fiscal document blithely ignores the issue, despite the fact that their lack of policy direction in the last few years has been the major contributor to the price surges that are scorching household and business budgets. There’s some pointless extra money for coal seam gas, the removal of some funds for carbon capture (finally) and some previously promised funds for solar thermal (about time), and even another thought bubble on Snowy Hydro – this time to buy it out from the state governments. See Matt Rose’s article for more details. But there is nothing on climate change, no grand vision on energy. There are no new funds for the Direct Action policy that Turnbull had once ridiculed as a fig leaf for a climate action, and nothing on what might take Australia along the path to the pledge it signed in the Paris deal – effectively to reach zero net emissions by 2050. As Labor’s Mark Butler noted this morning, the Coalition’s climate change policy has officially gone from that fig-leaf to a non-existent farce. Nearly three years after celebrating the dumping the carbon price (above), slashing the RET and ignoring expert advice (CCA and the Climate Council), the Coalition government has no actual policy, on energy or climate, and its negligence is adding to the stunning rise in electricity prices it is trying to blame on everything and everyone else. “Malcolm Turnbull, the Prime Minister who once said he didn’t want to lead a Liberal Party that didn’t feel as strongly about climate change as he did, is now the Prime Minister who has completely dropped any pretence of attempting to combat climate change,” Butler says in his statement, noting that climate change did not rate a single mention in the Budget speech. “As the central pillar of the Direct Action policy, the Emission Reduction Fund, runs out of funds, this budget delivers ZERO new policies or funding to drive down pollution and combat climate change. This budget allocates more new money to the Department of the House of Representatives than it does to tackling climate change. “Budgets are about choices and priorities, and this budget makes it perfectly clear the Turnbull government isn’t choosing a safe climate because they don’t think it is a priority. This budget finally makes official what we already know; this Liberal government is failing all future generations of Australians.” Read More here

State renewables bashing continues….

WATCH THE VIDEO FIRST: 16 March 2017, The Guardian, Josh Frydenberg escapes with dignity (mostly) intact after Jay Weatherill’s Adelaide ambush. I’ve read somewhere that an unnatural quiet presages an incoming tsunami. And so it was on Thursday, when the South Australian premier, Jay Weatherill, and the federal energy and environment minister, Josh Frydenberg, sat up in dignitaries’ row, straight-backed, avoiding eye contact, at the unveiling of a virtual power plant in a suburban garage in Adelaide. Weatherill’s jaw might have been just that little bit fixed, and Frydenberg’s cheeks just that little bit rosy as he found himself squeezed between a premier and his treasurer, Tom Koutsantonis, but the platitudes were dutifully mouthed. It seemed a bit odd that two politicians who have been going at each other hammer and tongs at a distance of hundred of kilometres for the best part of six months would be suddenly sitting together in a garage in Adelaide, with their energy plans splayed across their chests like shields. It seemed a bit off script. The whole purpose of a whipping boy (and that’s the role the Turnbull government has sought to cast South Australia in, Jay Weatherill, chief occupant of the naughty corner) is to remain at a discrete distance. In the corner. In the corridor outside. Banished. Rather like that virtual power station in the Adelaide garage, the Turnbull government versus Jay Weatherill is supposed to be a virtual boxing match, entirely bloodless. It’s just meant to crackle and hiss, the epitome of Australia’s busted, conflict-addled, half-unhinged politics – just some cheap static on the airwaves and the interwebs.What passes in this country for political discourse mirrors the casual viciousness of contemporary culture, where the hardest smackdowns are reserved for people we don’t need to make eye contact with. We rage most against the people we are highly unlikely to meet.Canberra v Adelaide is the political equivalent of the vitriolic text, or the social media troll. Weatherill wasn’t meant be there, in the room, sitting right there, when you are bagging him – he’s meant to be somewhere else. But there he was, like an Easter Island statue. Present. And not moving. Weatherill in Labor politics is known for his toughness. Frydenberg sets great store on being genial. Oil was about to meet water. Read More here

8 March 2017, Renew Economy, Queensland govt slaps down LNP, Murdoch over renewable scares. The Queensland government has attacked the LNP opposition and the Murdoch media for unfounded, baseless and “lazy” criticism of its plans to source 50 per cent of its electricity needs from renewable energy by 2030. The conservative LNP has been getting a big run in the Murdoch press with a new anti-renewables campaign, which has wound up significantly since the start of the year with a host of new solar projects that will add 1GW of solar power to the state’s grid….. That means that the Queensland government will not be in the same position as South Australia, which has had to watch with growing frustration as the private owners of the biggest gas plants in the state decide not to switch on during high demand periods, claiming they can find no economic incentive to help keep the lights on for their customers. On the subject of South Australia, premier Jay Weatherill said the state had no intention of rowing back on its 2025 target of 50 per cent renewables, saying to do so it would have to effectively “physically prevent” developments in their tracks. That much is true, because the build-out of the Hornsdale wind farm and the Tailem Bend solar project will take the state to 50 per cent wind and solar by the end of this year. Weatherill says the biggest threat to power prices in South Australia is the lack of competition among generators, something that can addressed by having more renewable energy and other technologies such as battery storage. Read More here

8 March 2017, Renew Economy, Queensland govt slaps down LNP, Murdoch over renewable scares. The Queensland government has attacked the LNP opposition and the Murdoch media for unfounded, baseless and “lazy” criticism of its plans to source 50 per cent of its electricity needs from renewable energy by 2030. The conservative LNP has been getting a big run in the Murdoch press with a new anti-renewables campaign, which has wound up significantly since the start of the year with a host of new solar projects that will add 1GW of solar power to the state’s grid….. That means that the Queensland government will not be in the same position as South Australia, which has had to watch with growing frustration as the private owners of the biggest gas plants in the state decide not to switch on during high demand periods, claiming they can find no economic incentive to help keep the lights on for their customers. On the subject of South Australia, premier Jay Weatherill said the state had no intention of rowing back on its 2025 target of 50 per cent renewables, saying to do so it would have to effectively “physically prevent” developments in their tracks. That much is true, because the build-out of the Hornsdale wind farm and the Tailem Bend solar project will take the state to 50 per cent wind and solar by the end of this year. Weatherill says the biggest threat to power prices in South Australia is the lack of competition among generators, something that can addressed by having more renewable energy and other technologies such as battery storage. Read More here

11 February 2017 The Guardian: Watching politics builds a high tolerance for hypocrisy and humbug, but even I am aghast at the Coalition’s antics this week – fondling a lump of coal in parliament while accusing the opposition of an “ideological approach to energy” and negligence in policy planning. Seriously. There’s a long list of blame and shame for Australia’s threadbare climate and energy policy, and the failure to plan for an energy market crisis that experts have warned about for years. But Malcolm Turnbull’s Coalition takes out first place. Arguably all sides of politics have made mistakes or miscalculations to get us to this point of omni-failure – high prices, blackouts and an inability to reduce electricity sector emissions – and yes, ideology has played a part: mostly the climate-change denying, renewables-are-a-socialist-plot ideology espoused by sections of the Liberal and National parties that once upon a time, a long time ago, Turnbull also railed against. Before we untether from reality entirely and drift off into a Trump-like universe where truth belongs to whoever delivers the best poll-driven lines or brings the dumbest prop to question time, let’s hammer down a few facts. Because we aren’t reviewing bad theatre here and when some commentators opine about whether Turnbull’s lines will “work”, or how funny the whole thing was, what they are really assessing is whether the prime minister can successfully, and in broad daylight, shift the blame for a monumental stuff-up, while apparently proposing solutions that will make it substantially worse in every regard. Since it’s our job to point out things like that, here are a few facts that undermine the “coal comeback” PR strategy that started rolling out sometime last year:

- Renewable energy is not “causing” blackouts.

- Renewables cannot take the blame for the recent rise in prices.

- New coal-fired power stations are not going to be built.

- Even if they were built, power from new highly-efficient coal-fired power stations would not be cheaper.

- Governments could always reduce the strain on the system and help avoid blackouts by reducing energy demand but schemes to reduce demand at times of peak power usage

- And finally, as business and industry and environmentalists and pretty much everyone who looks at the evidence (including, a while back, Turnbull) have been saying for years, the very best thing governments could do to encourage investment and a sensible low-cost transition to cleaner generation is come up with a bipartisan policy, such as the energy-intensity carbon scheme that had bipartisan political support, the backing of industry and could have reduced power prices while also bringing emissions down.

7 October 2016, Renew Economy, Finkel to lead NEM review, but states hold to renewable targets. Federal and state governments have agreed to an independent inquiry into the rules governing Australia’s energy markets, but the states have resisted attempts by the Coalition to force them to back away from their individual renewable energy targets. The hastily called meeting, held in Melbourne after the Coalition decided to use the South Australia blackout to attack state-based renewable energy initiatives, broke up with no agreement about individual renewable energy targets. But they did agree to an independent review that the federal government says will provide a “blueprint” for Australia’s power security to be led by chief scientist Dr Alan Finkel. There will be two other members, although they have not been named. States expressed hope that the Finkel report would move towards a more integrated response and market framework. Finkel, a keen supporter of nuclear, has also expressed his interest in solar and storage. “My vision is for a country, society, a world where we don’t use any coal, oil, natural gas; because we have zero emissions electricity in huge abundance and we use that for transport, for heating and all the things we ordinarily use electricity for,” he said during a media event relating to his appointment. “With enough storage, we could do it in this country with solar and wind,” Finkel said at the time. The appointment of Finkel was pushed by South Australia. It was supported by other states, but they insisted for other members on the panel who had experience of energy transitions. Read More here